IT WOULD TAKE many pages to list significant buildings in Seattle that have been lost in the past 170+ years, as natural disasters (fires, earthquakes) and man-made change (regrading, highways, commercial and residential construction) have reshaped the topography, replaced older buildings and filled open space.

The historic preservation community tries to get the word out that in the continuing push for sustainability, cities should encourage maintaining and upgrading old buildings. It is one of the best ways to improve the environment — preserving a building is greener than building green from scratch, and can make good business sense. Unfortunately, urban growth and the buzz about “building green” often overshadow the value of the old buildings that stand in the way.

Some older buildings live on in bits and pieces, for better or for worse. Let’s call them an outdoor art gallery: fragments of buildings that once stood proudly to enliven streetscapes with their brick, stone or terra-cotta facades; welcoming entrances; and elegant ornamental features from top to bottom. Now they serve as gateways to new construction — retained historical facade pieces. Some are well done; others are ungainly and mismatched accessories to concrete, glass and steel-walled construction that make observers wonder, “Why bother?”

Several buildings that were utilitarian workplaces for commercial laundries, warehousing or manufacture — some of them designated landmarks — have undergone what preservationists label “facadectomies.” Given that the alternative to facade preservation is likely demolition, we need to rely on the sensitivity and design talents of architects and developers to find solutions that respect and relate to historically significant components rather than simply doing a “cut and paste.” It isn’t surprising that so many of the workhorses of the early 20th century have been sacrificed for higher-density uses in re-imagining the Denny Triangle, Cascade, South Lake Union and Pike/Pine neighborhoods.

Let’s start in South Lake Union and make our way through Seattle for this selective journey through our history’s building fragments.

Pacific Lincoln Mercury and William O. McKay Ford showrooms

Westlake Avenue North and Mercer Street

1922

When it was determined that the widening of Mercer Street would require razing the Pacific Lincoln Mercury and William O. McKay Ford automobile showrooms, buildings that were settling and would have been challenging to move, Vulcan Real Estate, with the expert efforts of BOLA Architecture + Planning, took the extraordinary step of preserving the significant terra-cotta facades by carefully deconstructing, cleaning, repairing, labeling and storing them, along with stone, carved wood window frames, leaded glass, the central stair, marble — even the ceramic-tile fountain of the Pacific McKay showroom — for eventual reinstallation on a new building at the site. While one could argue the merits of the Allen Institute’s new building design, as it bears no relationship in scale or materials to the reconstructed showroom, it does demonstrate a willingness to preserve an important landmark that speaks to an era when the automobile showroom had the glitz of a motion-picture palace.

The Seattle Times building

1120 John St.

R.C. Reamer, 1930-31

In 1916, The Seattle Times building on Olive Way, faced in ornamental terra-cotta and designed by Bebb & Gould, reflected the best qualities of American Renaissance architecture. When the newspaper moved from its signature flatiron building at what is still referred to as Times Square to Fairview Avenue and John Street in 1930-31, modernistic design aesthetics influenced architect R.C. Reamer to develop a headquarters that emphasized mass and proportion with Indiana limestone. The window spandrels were faced with decorative cast-aluminum panels in abstract motifs, and there were references to Classicism with fluted piers and simple cresting at the parapet. The aluminum entrance door grille, decorated with octagons and floral, spiral and wave motifs, was inspired by contemporary French decorative metalwork by Edgar Brandt and others at the 1925 International Exhibition of Modern Decorative and Industrial Arts in Paris, and incised floral ornament in limestone was used in the vestibule. The printing plant to the north used exposed concrete and industrial windows to echo the scale and proportions of its refined office building neighbor.

In 1996, The Times building was designated a city of Seattle Landmark. Fast forward to 2013, when The Seattle Times sold the building. Onni Group, a Vancouver, B.C., developer, built housing on the former parking lot to the south and planned two office buildings with retail on the north block, where The Times building sat. Because of its landmark status, an agreement was reached to preserve the south and east facades and incorporate these into new construction designed by Perkins&Will. The project has been stalled, leaving the excavated site and a forlorn, graffiti-covered remnant of a distinguished Art Deco contributor to the city.

Troy Laundry towers and historic facade

Fairview Avenue and Republican Street

1927

The Troy Laundry, originally located on East Republican Street, moved to its new, larger facility in 1927. Behind its handsome brick and terra-cotta facade was one of the largest commercial laundries in the city before The Seattle Times acquired it for its expanded operations. Designated a city of Seattle Landmark in 1996, its principal facades now form the base of two setback office towers developed by Touchstone. Its horizontal color banding references the terra-cotta-trimmed brick band of the historic building’s parapet. And in a further acknowledgment of the laundry’s history, an interior arcade displays artifacts, including a marquee sign, an operating laundry scale and benches made from old boiler valves.

Firestone Rubber Company

400 Westlake Ave. N.

1929

On Jan. 24, 1930, The Seattle Daily Times extolled the Firestone Rubber plant as “one of the most modern tire structures in the West,” equipped with “thousands of dollars of ‘almost human’ mechanical equipment” and boasting a “one-stop shop for automotive service, a new idea for the era.” On its website, Martin Selig Real Estate touted the modern redevelopment of the Firestone Rubber Company as “a preserved landmark, in harmony with a modern addition.” But is it? How is it in harmony with the 15-story glass curtain wall that hovers over it, albeit with a token setback behind the old building’s parapet? And one can question whether the Firestone is truly a “preserved landmark” when, in fact, it is only a shell framing a completely new building.

Capitol Hill Auto Row

Seattle’s Pike/Pine neighborhood historically housed automobile showrooms, supply houses and repair shops. Most were one- and two-story buildings with structures to allow for spacious ground floors that could accommodate movement and servicing of cars. Given community concern about the number of these signature buildings being razed, the city established a Pike/Pine Conservation Overlay District with guidelines that have been expanded and amended “to strengthen measures for maintaining and enhancing the character of the Pike/Pine neighborhood.” The results of these efforts have been mixed. And they bring into question whether it is better to make the effort to preserve these pieces that no longer have any connection to the multistory buildings constructed behind their walls, or to let them rest in peace.

In her insightful article in ARCADE, “What Price Facadism,” Eugenia Woo, Historic Seattle’s director of preservation services, addressed the meshing of old and new by saving the most visible part of an older building, rather than rehabilitating it and adapting it to new uses, as ignoring and destroying the essential meaning of the structure.

“Stripped of everything but its facade, a building loses its integrity and significance, rendering it an architectural ornament with no relation to its history, function, use, construction method or cultural heritage … When its defining features are mostly removed and no longer part of an integrated whole, a building no longer demonstrates its authentic self. Further, the scale and massing of the new building change the rhythm and feel of a block and neighborhood … Facadism is less preservation and more a begrudging compromise between the past and the future.”

These are complicated projects that, along with the design and permitting process, often require additional time for public and city input. While changes to landmarked properties go through a series of reviews by the Seattle Landmarks Preservation Board and its Architectural Review Committee, even nonlandmarked buildings in the Pike/Pine conservation district are subject to community meetings and changes to the initial proposals. This occurred when the developers of the Phil Smart Mercedes-Benz dealership, a full block from East Pine to East Pike Street and Belmont to Boylston avenues, had to consider a number of buildings of different types and functions.

Some projects preserve significant facades and do a generally respectful incorporation of these. Pedestrians passing by experience the brick, colored tile or cream terra-cotta embellishments and might realize that a multistory building rises above it only if they look up. If you are curious, walk these blocks and come to your own conclusions about whether they are successful or disappointing. The Packard Building is at the corner of 12th Avenue at East Pine Street. The 1917 Kelly-Springfield Building, which originally housed a motor truck company, is at 11th Avenue between East Pine and East Pike streets. And across the street, the 1926 Sunset Electric Company, a supplier of automobile electrical equipment with an appliance showroom, is at 1530 11th Ave.

The Burke Building

Second Avenue and Marion Street

Elmer Fisher, 1889

One of the tragic early losses in Pioneer Square was the red brick and stone Burke Building. Fisher’s signature post-Great Seattle Fire buildings sent an optimistic signal about Seattle’s confident growth. In 1973, its replacement, the General Services building for the federal government (Henry M. Jackson Federal Building), paid homage to its predecessor, largely because architect Fred Bassetti designed a brick plaza and stairway from First Avenue to Second Avenue that incorporated the main entrance arch and numerous salvaged terra-cotta panels and parapet embellishments into his design. It made for a gentle, artful discovery as people ascended or descended. Critical repairs are now needed because of leaks and damage to the garage underneath, and it remains to be seen how this might impact this gift to the street.

Standard Record & Hi-Fi

1028 N.E. 65th St.

1947

On Northeast 65th Street in the Roosevelt Business District sat a vestige of 1940s-era commercial Seattle: Standard Record & Hi-Fi. Opened in 1947 as Standard Radio, it was the post-World War II equivalent of the Apple Store, and its products were as much in demand as the iPhone is today. Its iconic streamlined facade was outfitted in structural glass veneer. The curving sheet metal canopy and neon lighting completed the look. These were identifiable features that set this and other progressive Streamline Moderne retailers apart from the more traditional 1920s-era brick of their storefront neighbors.

When it closed, the store’s display windows announced that it was part of the new Sound Transit light rail station. In fact, it was not a part of it but would be a casualty of the construction. Responding to community concerns, the North Link project offered: “Although the building is not officially designated a landmark, Sound Transit recognizes its importance to the neighborhood. In response to community requests, Sound Transit will attempt to preserve the ‘Standard’ sign or other components of the building and will consider how they might be incorporated into the station design.” To its credit, the Sound Transit team salvaged and restored the signage and was able to remove a small amount of glass tile that does welcome riders to the station’s Northeast 65th Street entrance.

The Metropolitan Tract

Howells & Stokes

1908-15

The plan for the Metropolitan Tract, the progressive civic center developed on the 10-acre site of downtown’s Territorial University, included a harmonious grouping of brick and terra-cotta office and retail buildings facing each other along Fourth Avenue. The Cobb Building remains, but the White-Henry-Stuart buildings that were built in sections and covered the entire east side of Fourth Avenue were demolished for the Rainier Square Tower and shopping mall in 1974. Salvaged at that time were several of the terra-cotta busts of American Indian chiefs with ceremonial headdresses who were often mistaken for Chief Seattle. Local modeler Victor Schneider was responsible for fabricating the clay molds to be fashioned into the multiple terra-cotta pieces to form each relief. Several variants of these pieces still can be seen — at the entrance to the Cobb Building, the Washington State Convention Center lobby on Pike Street, outside the Museum of History & Industry and at the Daybreak Star Indian Cultural Center in Discovery Park.

Perry Hotel

1019 Madison St.

1906-07

“Perry Flats underway … New York Apartment house transplanted in Seattle,” announced the Seattle Post-Intelligencer on Oct. 21, 1906. Joseph S. Coté and W. Marbury Somervell, who had been sent to Seattle by the New York firm of Heins & LaFarge to supervise construction of Saint James Cathedral, designed this eight-story brick building on the southwest corner of Boren and Madison. By 1910, due in part to completion of the nearby Sorrento Hotel, which enticed some residents to relocate there, the Perry’s popularity declined. In 1915, Mother Frances Xavier Cabrini purchased the property and turned it into the Columbus Sanitarium, later renamed Columbus Hospital. The building had structural issues that would have made repairs and reuse costly. This led to its razing in 1995 for low-cost housing for the elderly. The Cabrini organization intended to incorporate much of the terra-cotta ornamentation into a new, larger building, but this did not happen in the final abbreviated development. Only the terra-cotta entrance was preserved and installed into the Cabrini Medical Tower to the south on Boren Avenue near Madison Street, with several additional remnants displayed in the lobby.

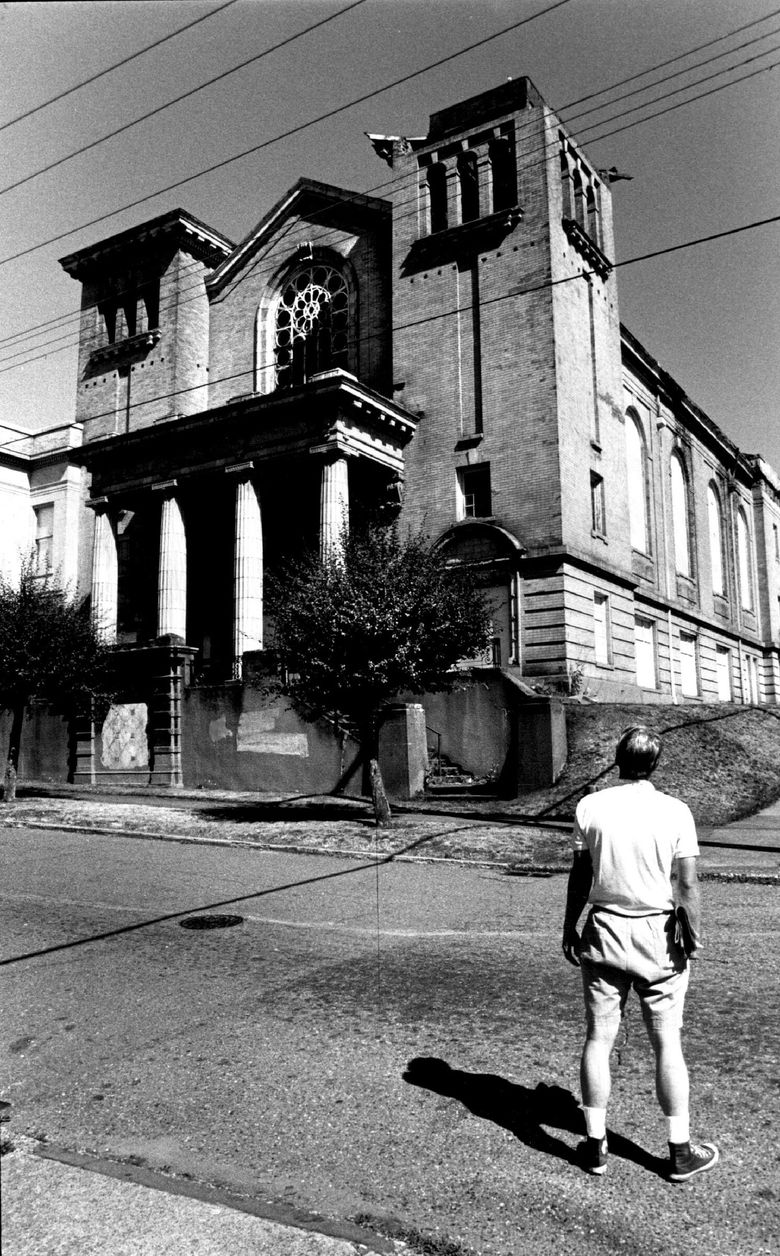

Temple De Hirsch Sinai

15th Avenue East and East Union Street

J.F. Everett, 1907-08

Temple De Hirsch Sinai congregation is the oldest (1897) and the largest Jewish congregation in the Puget Sound region. Its members include civic leaders and businesspeople who contributed greatly to the growth of the community and to the Northwest. Named for Baron de Hirsch, a benefactor who assisted Eastern European Jews in their efforts to reach America and start new lives, the temple was completed in 1908 in the Neoclassical style. Clad in buff-colored brick with terra-cotta trim, its west front consisted of a Doric-columned entrance portico flanked by two substantial bell towers. Both towers originally terminated in rich Baroque belfries and cupolas, later removed. The temple, long vacant and decaying, was demolished in 1992, and only a few remnants of the dignified facade stand watch over the site today.

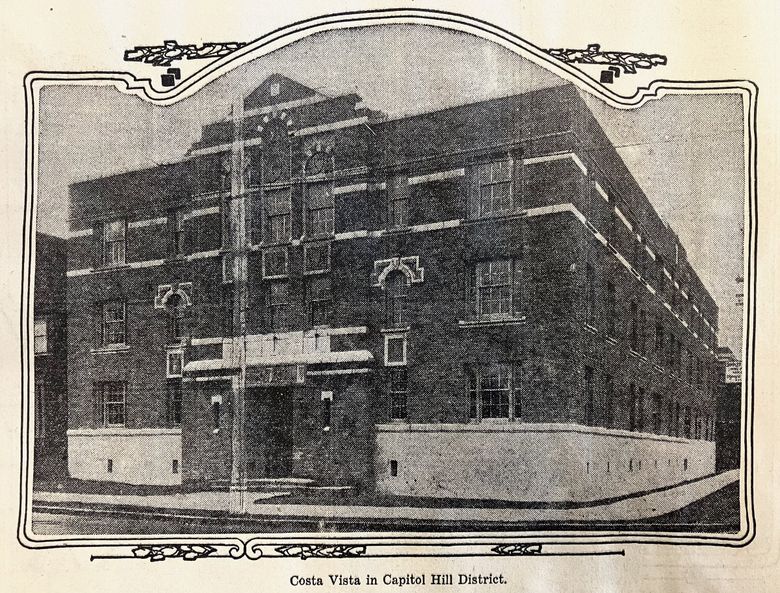

Costa Vista apartments / Group Health Cooperative / Kaiser Permanente Washington courtyard

Originally 15th Avenue North and East John Street

J. Lister Holmes, 1926

During the rapid development of Capitol Hill for multifamily apartments, The Seattle Daily Times on Dec. 5, 1926, featured a photograph and an article announcing the opening of the Costa Vista, a “beautiful brick structure of 28 apartments.” It described its style as “of the Mediterranean type executed in buff tapestry brick and glazed terra-cotta.” The Medical Security Clinic had acquired the 55-bed St. Luke’s Hospital on Capitol Hill. It was purchased by the fledgling Group Health Cooperative (GHC) in early 1946, which maintained its clinic downtown in the Securities Building. When rent was hiked, GHC negotiated with then-owner Mrs. Westover to purchase the Costa Vista apartment building in 1951, and the new clinic opened there in 1952 after extensive remodeling. St. Luke’s Hospital and Costa Vista were razed for a new 173-bed hospital building in 1960. The colorful floral terra-cotta embellishments from the top of the Costa Vista can be enjoyed from the Kaiser Permanente Washington garden courtyard.

Terminal Sales Annex building/Puget Sound News Company

1931 Second Ave.

Bebb & Gould, 1915

Lest we think that the days of sacrificing the building but doing token acknowledgment by keeping the facade are over, other projects do appear. The latest is a proposal for a 42-story hotel and residential building to rise around and over the elegant Gothic Revival terra-cotta-clad Terminal Sales Annex building (originally Puget Sound News Company). In 1915, Bebb & Gould was a master of several architectural idioms, judging from its Renaissance Revival Seattle Times building and the Collegiate Gothic quadrangles and library at the University of Washington. The proposed redevelopment of the Terminal Sales Annex site goes back a decade. The current design by Ankrom Moisan architects and Kengo Kuma & Associates has faced numerous revisions in consultation with the Seattle Landmarks Preservation Board, which recently approved the project for a second time because the developer sought a different design and program. Given the number of apartment projects that have stalled downtown and in the Denny Triangle, it might be years before any activity begins here.

Editor’s note: An earlier version of this story incorrectly identified the developer of the Troy Block. It was Touchstone, not Vulcan.