By

Before the pandemic, most fentanyl-related overdoses reported in the Seattle area involved people with homes.

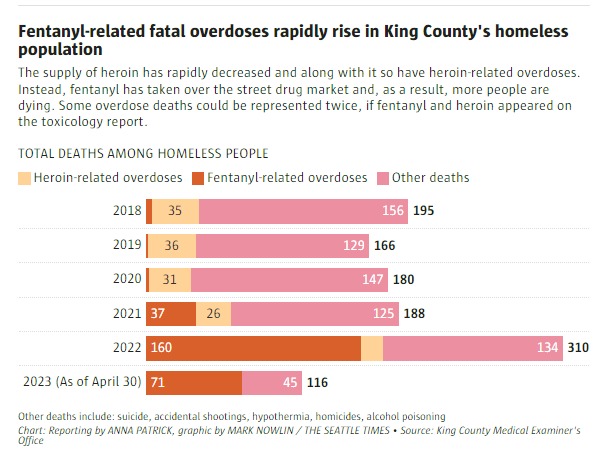

They started around 2016, said Brad Finegood, who leads the opioid and overdose response for Public Health – Seattle & King County. In 2020, two deaths of homeless people were related to a fentanyl overdose. Two years later, that number leapt to 160.

And the death rate is still rising. Though homeless people make up around 1% of King County’s population, they are vastly overrepresented in the deadly statistics.

As of May 17, 20% of the county’s 530 overdose deaths this year — 104 people — were those living in shelter or in vehicles, encampments and outside — a rate on track to break last year’s record as the deadliest for overdoses in King County’s homeless population.

Homeless people are one of Washington’s most vulnerable and hardest hit groups in the current fentanyl epidemic due to market forces and the harsh realities of living outside with less access to treatment and greater chances of being isolated.

“It’s really the perfect storm,” Finegood said.

Seattle Mayor Bruce Harrell has said the city needs to do more, but other than increasing attempts to arrest drug dealers, officials have been slow to roll out immediate help for people living unhoused.

Outreach workers say the mayor’s increased encampment clearings may be making things worse.

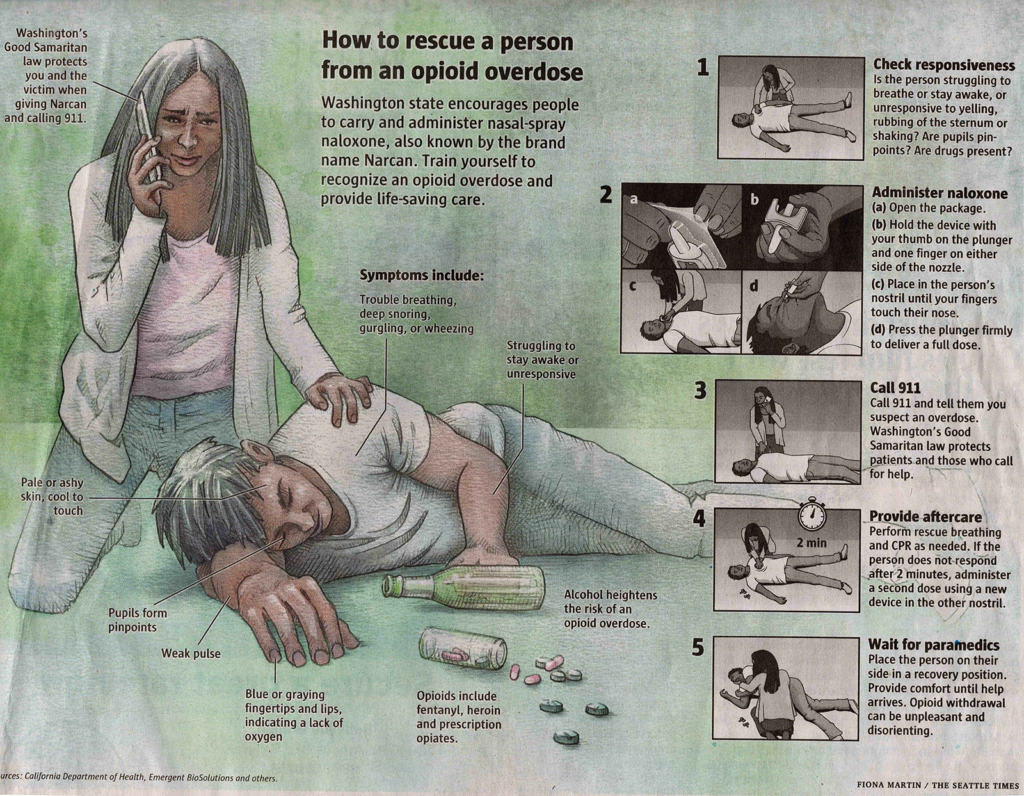

Public health officials have been focused on education and harm reduction, handing out overdose reversal drugs and fentanyl testing strips.

Due to the high visibility of unsheltered people, state and local efforts to criminalize drug possession could disproportionately send them to jail, which has been shown to increase the chances of overdose upon release.

As the death toll continues to climb, Finegood said he’s never seen a lethal drug crisis move so rapidly.

“It’s even continuing to evolve right before our eyes,” he said.

How did we get here?

When fentanyl first began to enter the street drug market, many of the homeless patients at the Downtown Seattle Public Health Center’s Pathways opioid-use treatment program said they were “not touching that stuff,” said Dr. David Sapienza.

While not everyone surviving homelessness becomes a drug user, many people who have been homeless a long time or struggle with untreated physical and mental health issues do turn to drugs to cope with the brutality of surviving on the street.

- Fentanyl has devastated King County’s homeless population, and the toll is getting worse

- How fentanyl became Seattle’s most urgent public health crisis

- What most of us think about opioid treatment is wrong, UW researcher says

- Fentanyl-related deaths among kids rising sharply, study finds

- WA urges young people to carry naloxone; here’s where to get it

Methamphetamine use remains common among people who need to stay awake at night to protect their belongings and look out for possible threats. Heroin and opioid pills have been used as a way to feel relaxation, euphoria and an escape from pain.

Winter said she didn’t think much about drugs until she became homeless after an eviction about five years ago. But there’s no way she would have survived life outside if she didn’t have a way to numb her senses, said Winter, who asked to use a nickname because of the stigma around drug use.

At first, she started using meth, then later added heroin. But about six months ago, she couldn’t find it, she said. Fentanyl was the only choice.

“I held out as long as I could,” Winter said.

She sometimes uses fentanyl with meth, a common combination found in overdose deaths.

Courtney Pladsen, clinical director of National Health Care for the Homeless Council, first saw the arrival of fentanyl in homeless communities in 2017 on the East Coast, years before it made its way west.

With heroin, it was easier for people to know how much they needed to get through their day and avoid withdrawal symptoms. But fentanyl’s increased potency and unreliable dosage makes it nearly impossible to know exactly how much they’re taking, thus increasing the chance of overdosing.

“People don’t want to die, but they don’t want to get sick from withdrawal either,” she said.

Many West Coast cities are now reporting catastrophic impacts.

In Los Angeles County, deaths of homeless people rose by 55% from 2019 to 2021, largely driven by fentanyl. And in San Francisco, the number of homeless deaths doubled from March 2020 to March 2021, with the majority of deaths due to fatal overdoses.

What makes survival harder

These days, Winter can buy a blue fentanyl pill for $2. If she buys in bulk, she said, pills can go for as low as 80 cents apiece.

The synthetic opioid is 50 times more powerful than heroin, but has a shorter half life. Winter said that two pills can help her feel OK for about one or two hours, which means she’s using about 30 to 40 pills a day.

“It’s like a dragon,” she said. It creates a vicious cycle of seeking, using and then seeking again.

She is surrounded by people also trapped in that cycle. She’s revived 13 people from overdoses over the past two years, Winter said, and knows of several people who have died.

Just like heroin and morphine, fentanyl binds to the body’s opioid receptors and activates the parts of the brain associated with basic drives for safety and survival. It also slows breathing, decreasing the amount of oxygen reaching the brain, which can cause someone to die.

Amanda Kerstetter, a harm-reduction specialist for REACH, one of the largest homeless outreach providers in the county, advises her clients to leave the opioid-overdose reversal drug naloxone — known by the brand name Narcan — next to them when they are using, in case of an overdose.

That requires someone else to be around and to be alert. An increase in encampment clearings by the city of Seattle has made it harder for fentanyl users to have trusted neighbors around to watch out for them.

Dawn Shepard, program manager at REACH, knows this firsthand. When she was homeless, the first time she tried fentanyl she remembers having her purse next to her. By the time she came to, it was gone.

“The impairment is on a totally different level,” she said compared to heroin, which she was using regularly at the time.

Fentanyl dulls, or entirely eliminates, the ability to look for threats — a skill many people on the streets hone.

“Survival skills are one of the few things that keep people alive outside,” Shepard said.

Outreach workers say the encampment clearings create a struggle to stay connected with clients because they are constantly being moved from one place to another.

A labor shortage in homeless services during the pandemic has also stunted outreach work. There are fewer people with less experience, meaning it takes longer to build connections and gain trust with clients — critical steps to help someone find housing and treatment, said Semone Andu, regional health administrator for King County’s Healthcare for the Homeless Network.

“We do not have the luxury of time,” Andu said.

Actions on the horizon

State and local officials have started to mobilize around this population, but many of the solutions are months or years out.

Harrell recently announced a new executive order that includes expanding the Seattle Fire Department Health One team to add an overdose-response unit, increasing access to opioid-reversal drugs, and incentivizing people to accept treatment using gift cards.

The mayor’s office said some of the programs are planned to start this summer.

“The fentanyl epidemic is killing people across our city and across our country. Already among Seattle’s most vulnerable, people experiencing homelessness are disproportionately at risk — fentanyl is a fatality multiplier,” Harrell said.

The City Council previously budgeted money for a site where people could use drugs with supervision and medical help, but never created it.

And a state law passed last week that defines penalties for drug possession and use also paves the way for “health engagement hubs,” where people can walk in off the street to receive treatment for substance use disorders, among other things.

In the shorter term, Evergreen Treatment Services, which provides addiction treatment in Seattle, will launch a mobile methadone dispensary Monday to help people living outside access treatment. Medications that bind to opioid receptors in the brain but don’t cause highs are one of the most effective methods to treating fentanyl dependency.

Methadone usually requires patients to visit a treatment center on a regular basis, which is difficult for people without reliable access to transportation.

Sapienza, at Downtown Public Health Center’s Pathways program, said that more low-cost, low-barrier treatment options could make a huge difference in helping his homeless clients enter and stay in recovery. For example, in many other countries methadone is easier to access because it can be prescribed by a doctor in an office visit and filled at a nearby pharmacy, Sapienza said.

Recently, the federal government passed a law ending restrictions on which doctors could prescribe buprenorphine.

Recovery harder without housing

More than half of Sapienza’s patients experience withdrawal in a tent, shelter or outside in the elements, often without access to public restrooms when the nausea, vomiting and diarrhea set in.

Trying to get off fentanyl is no easy task, even for those with more resources. The anxiety, depression and other symptoms can last for days before treatments begin to help someone feel normal again.

“With everything else that’s going on in our patients’ lives, it’s pretty hard to navigate not feeling well for multiple days,” he said.

Sapienza said that for most of his patients, treatment takes a winding path of recovery and relapse, which requires consistent long-term support.

And not having a home makes that even harder.

Everett Croak, a 34-year-old veteran, was up to a gram and a half of fentanyl a day before he went to jail in February.

Living in a tent in the Chinatown International District, he was mainly boosting, or reselling, stolen items to pay for the synthetic opioid that had taken over his life in the last year and a half.

“It absolutely grabs you by the tail and holds on,” Croak said.

He went into detox in the Des Moines jail and describes it as having the worst flu imaginable multiplied by 10.

By early May he was living outside again and said he wanted to find housing using veteran services. He was thinking about selling his abstract artwork near Pike Place Market.

After going through detox, he said, “It’s like I’m free now.”

He’s hoping he can keep it that way.

Anna Patrick: apatrick@seattletimes.com; on Twitter: @annaleapatrick.