HOW OFTEN HAVE YOU gone into a commercial or civic building, a restaurant or a newly remodeled shop in an older building and looked up at the ceiling, only to face galvanized metal HVAC ducts and an array of variously colored pipes? Or looked down at the raw concrete underfoot, or around at unadorned columns and brick walls that never were meant to be seen, sheathed originally with lath and plaster and decorative molding?

It wasn’t always like this.

Earlier property owners and their architects and designers were expected to create enticing, dramatic and colorful spaces that elevated office workers, residents and tourists and enlivened their experiences.

Despite the loss of a large number of theaters and religious, civic and office buildings in Seattle, there are still some that elicit open jaws and “wows” from people seeing them for the first time — and even on second or third visits.

There also are some later additions that, thanks to a vibrant public arts program, have enlivened what could have been forgettable spaces.

Here is a sampling of wow-worthy architectural details from downtown and surrounding neighborhoods, arranged chronologically within each area. Some might be quite familiar. Others might surprise you … and give you a definite reason to venture out a bit. Look up from your devices and their virtual images, and take joy in actual, unique spaces that are irreplaceable.

Downtown Seattle

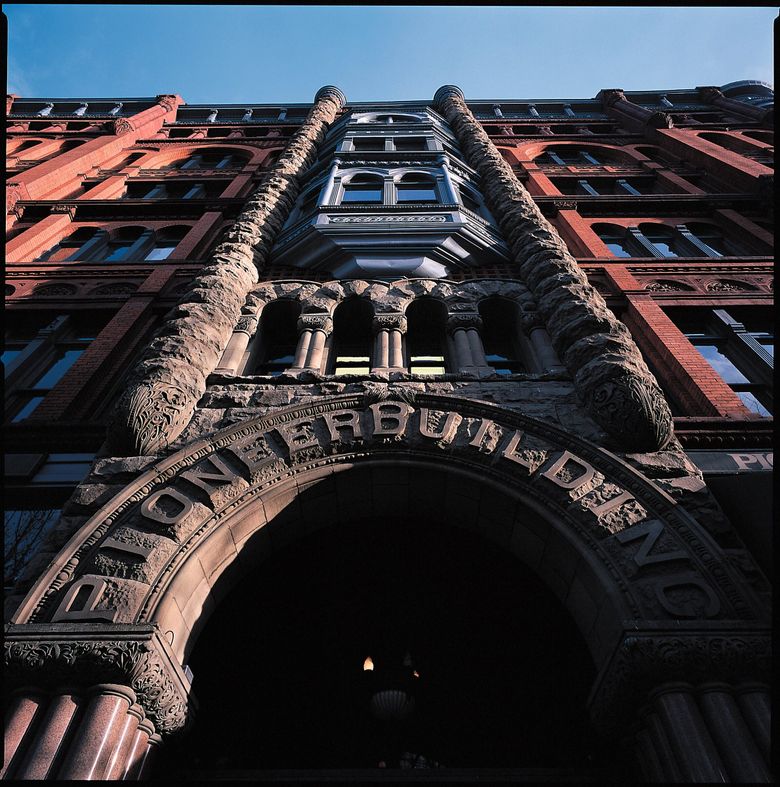

Pioneer Building

600 First Ave.

Elmer H. Fisher, 1889

Prolific architect Elmer H. Fisher had commissions to design a number of post-Great Seattle Fire buildings in the popular Romanesque style. This building was a focal point for the newly built business district. Its height and mass were permitted by the use of structural steel to support and span dramatic interior spaces. The Pioneer Building was constructed in two parts: The first was completed from the entrance to the corner bay, and the second north of the entrance bay.

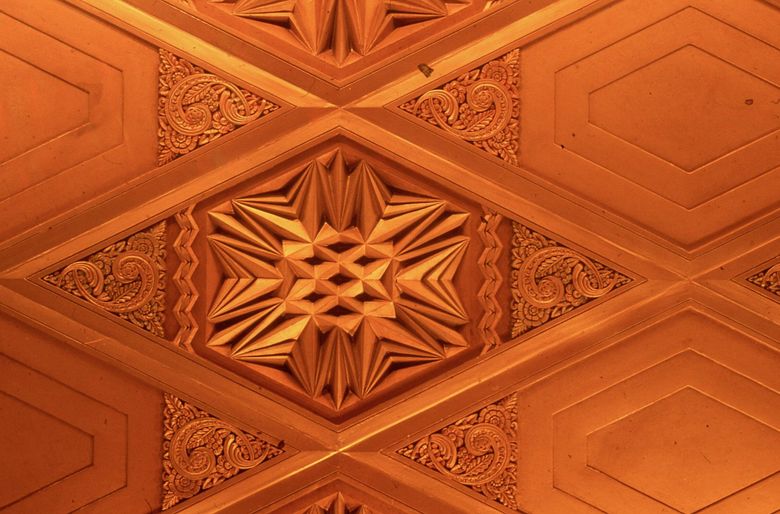

King Street Station

303 S. Jackson St.

Reed & Stem, 1904-06

James J. Hill commissioned the firm of Charles Reed and Allen Stem, designers of New York’s Grand Central Station, in 1904, and King Street Station opened in 1906. The marble and colored glass inlaid walls of the entrance foyer lead into a waiting room and balconies sharing a Classical revival vocabulary of coffered ceilings and Corinthian crowned piers.

L.C. Smith Building (Smith Tower)

506 Second Ave.

Gaggin & Gaggin, 1910-14

Lyman Cornelius Smith of Syracuse, N.Y., commissioned a Syracuse design firm to design a 600-office, 522-foot-high tower costing $1.5 million that would become the fourth-tallest building in the world, topped only by the Singer, Woolworth and Metropolitan towers in New York. Eight operator-assisted elevators originally served the building; two of them serve the tower portion, and one rises to the Chinese Temple Room at the 35th floor.

Arctic Club Building

700 Third Ave.

A. Warren Gould, George Lawton, 1913-17

The Arctic Club was a social club composed of the region’s prominent citizens and was headquartered in the Morrison Hotel at Third Avenue and Jefferson Street. As the club grew, a building on the corner of Third and Cherry was commissioned. Designed by A. Warren Gould in 1913 and completed in 1917, the cream-color terra-cotta-faced building provided flexible office space and beautifully detailed club interiors. Multicolored matte-glaze terra cotta in submarine blue and peach adorns the elaborate top story, main cornice and spandrel sections.

5th Avenue Theatre

1308 Fifth Ave.

R.C. Reamer, 1926

The 5th Avenue Theatre and the Italianate Skinner Building that surrounds it were designed by respected local architect R.C. Reamer. His early work included Old Faithful Inn and other lodges and shelters at Yellowstone Park. In Seattle, his firm was responsible for a number of prestigious buildings, such as the 1411 Fourth Ave., the Great Northern building, The Seattle Times headquarters and the Meany Hotel. The magnificent interiors of the 5th Avenue Theatre, opened in 1926, were inspired by the Summer Palace; the Temple of Heavenly Peace; and the Throne Room in the Hall of Supreme Harmony, the largest of the palaces at the Forbidden City, all in Peking (now Beijing).

Paramount Theatre

901 Pine St.

Rapp & Rapp; B. Marcus Priteca, 1927-28

Constructed during 1927-28 and opened as the Seattle Theatre, the 3,000-seat Paramount was billed as “the largest and most beautiful theatre west of Chicago.” Its architects, Rapp & Rapp, were responsible for the New York Paramount and many other picture palaces throughout the nation. In Seattle, they affiliated with B. Marcus Priteca, renowned for his beautifully designed and acoustically superb theaters for Alexander Pantages and the Warner Bros. and Orpheum chains.

Northern Life Tower/Seattle Tower

1218 Third Ave.

Albertson, Wilson & Richardson, 1927-29

As the first and finest example of the Art Deco skyscraper in Seattle and one of the showpieces of that style on the West Coast, the Northern Life Tower’s setback form and accentuation of verticality resemble Saarinen’s famed submission for the 1922 Chicago Tribune Tower competition. The lobby was conceived as a tunnel, carved out of solid rock, its sidewalls polished, the floor worn smooth, and the ceiling incised and decorated as a civilized caveman might have done it. Marble, intricate incised bronze panels and a gilt ceiling with low relief abstract patterns share a consistent set of motifs suggestive of Northwest Indian, Mayan and Chinese cultures. The building itself is crowned by three metal spires representing evergreens.

1411 Fourth Ave. building

R.C. Reamer, 1928-29

The last major project developed by lumberman and real estate entrepreneur C.D. Stimson was neither the largest nor the tallest Seattle office building, but at 15 stories, it was claimed to be the tallest in the city sheathed in stone, while its contemporaries were faced in brick with terra-cotta trim or in glazed terra cotta alone. The stone complements two other Reamer-designed buildings nearby, the Great Northern and Skinner buildings. Its boxlike modernistic style is defined by recessed spandrels, unadorned vertical piers, gently set back parapet pillars, and a vocabulary of French Art Deco and Celtic ornament at both base and crown. Located directly across from the Great Northern main ticket office, the building housed many of the city’s railroad and steamship lines, making Fourth and Union Street a transportation hub.

Exchange Building

821 Second Ave.

John Graham Company, 1929-31

The Exchange Building, built to house Northwest commodities and stock exchanges, opened its doors, ironically, in the year of the stock market crash. Most of its design scheme was borrowed directly from stylized floral designs from the 1925 International Exhibition of Modern Decorative and Industrial Arts in Paris, including baskets of stylized flowers and geometric and spiral borders and fill. The Second Avenue entrance lobby offers one of Seattle’s most theatrical experiences. Bronze ornament surrounding the directory highlights tulips that were grown locally before development of the Skagit Valley tulip fields. Wildflowers radiate from the mailbox, and the great wheat fields of Central and Eastern Washington are depicted prominently above the elevator doors. The Central Washington fruit-growing region is represented in the bronze surrounds of the elevators and in the vine and grape panels that originally decorated the exterior of the elevator doors. Wood stencil treatments around interior lobby doors and telephone booths consist of incised ornament of native flora and fauna.

Metro Transit Tunnel Westlake Station

TRA, 1989

Most transit riders these days have forgotten (or never knew) how much effort was put into defining the neighborhood character for each of the downtown transit stations. At the time, it was one of the largest public art projects in the nation. Westlake Station was the most elaborate of these, its platforms and stone-faced mezzanine designed to mirror the retail district above ground. While the three colorful enameled tile murals might capture most of the attention, two background works deserve appreciation: Jack Mackie crafted the floral terra-cotta tiles covering the south wall, and Vicki Scuri’s stitched fabric patterns, comprising 40 cream-colored tiles, reflect department stores on Pine Street including The Bon Marché, Frederick & Nelson and Nordstrom.

First Hill

Fourth Church of Christ, Scientist/Town Hall Seattle

1119 Eighth Ave.

George Foote Dunham, 1916-22

Dunham’s buildings for Church of Christ, Scientist congregations in Portland, Victoria and Seattle borrow from formal Greco-Roman classicism with a vocabulary of decorative capitals and pilasters and the extensive use of terra cotta, combined with a wealth of leaded and colored glass. The showpieces of the Seattle sanctuary are its stained and leaded glass windows and dome, designed and fabricated by Povey Brothers Glass Company of Portland.

Hotel Piedmont/Evangeline Young Women’s Residence/Tuscany Apartments 1215 Seneca St.

Daniel Huntington (Huntington & Torbitt) 1927-28

The rain- and cloud-filled skies of the Northwest inspired the well-to-do to make extended winter trips to Southern California. The C.D. Stimsons, for example, kept a cottage on the grounds of the Huntington Hotel in San Marino for much of the winter. Exposure to the southern climate and to its Spanish Colonial Revival legacy of stuccoed buildings with red tile roofs inspired local residents and their architects. By the mid-1920s, the Mediterranean and Spanish Colonial style brought visions of sunshine and warmth to Seattle. Architect Daniel Huntington’s Hotel Piedmont even went so far as to use a large quantity of art tile from the Malibu Tile Company to sheathe the street-level facades. After many years as a women’s residence hall for the Salvation Army, the building was converted to apartments in 1986 by Alexander & Ventura.

Doctor’s Hospital

909 University St.

George Wellington Stoddard, 1944; Dudley Pratt bas reliefs

Seattle’s eighth new hospital opened on First Hill in 1944: Doctor’s Hospital was on the site of the Rolland Denny home. The project of the King County Medical Service Corporation was financed by federal funds and matching funds saved over time by the nonprofit corporation. The first floor was dedicated to maternity and childbirth; the second floor included five surgeries, two wings of rooms for 80 patients, X-ray, laboratories, “frozen-section” rooms, and special facilities for bone surgery and urology procedures. In October 1975, the governing boards of three Seattle hospitals — Doctor’s, Swedish and Seattle General — agreed to merge under the name Swedish Medical Center.

Capitol Hill

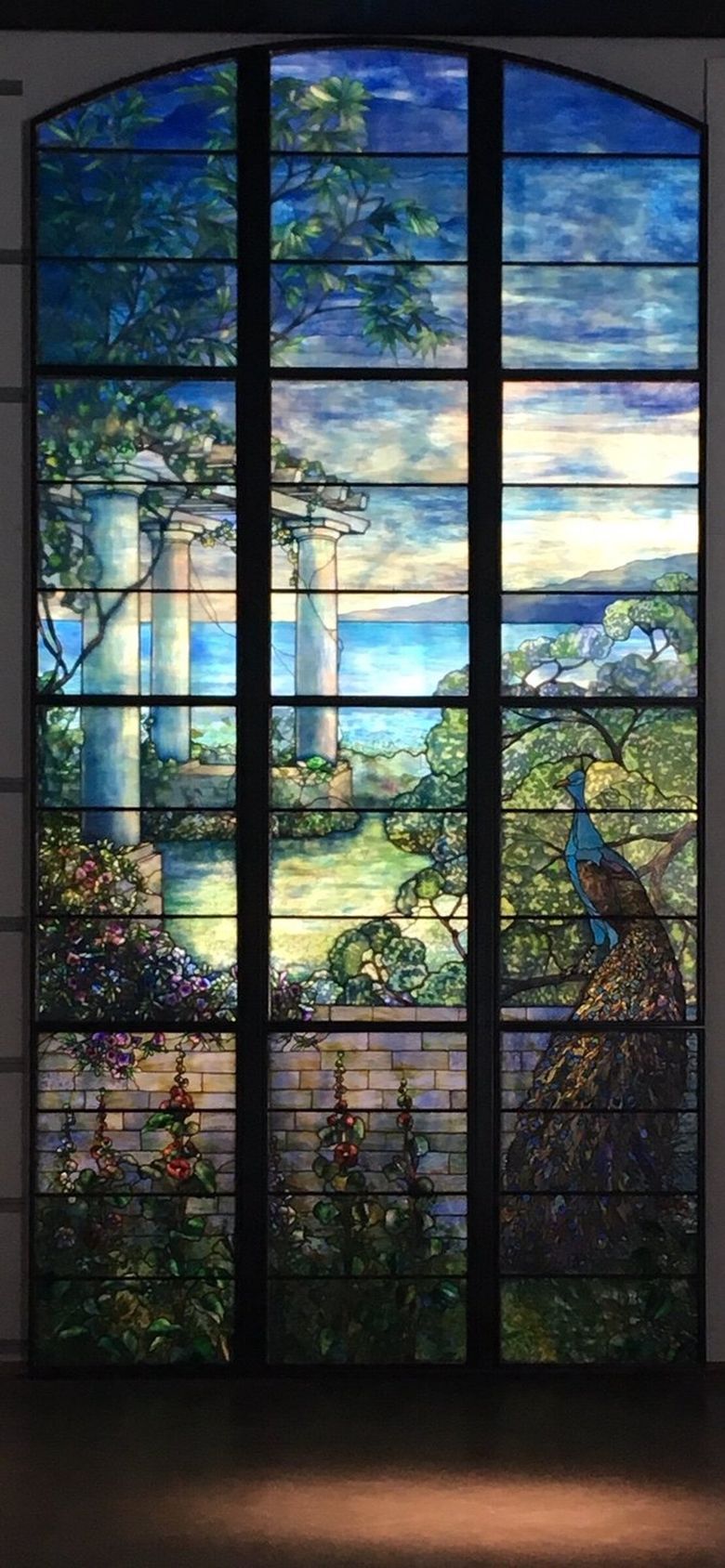

John and Eliza Leary Mansion/The Red Cross/the Episcopal Diocese of Olympia

1551 10th Ave. E.

Alfred Bodley, 1904-07

John Leary succeeded in lumber manufacture and sales. He also invested in coal mining, gas, water, railroading, land development, banking and marine navigation. In 1884, he served a term as mayor of Seattle, and later was a president of the Rainier Club as well as a regent of the University of Washington. His architect, Alfred Bodley, arrived in Seattle in 1904 from Victoria, B.C., and was commissioned to design what would be for a time the largest private residence in the city. The focal point was the baronial great hall, two stories in height and an essentially Renaissance Revival setting, with a towering stained-glass window of a peacock in a garden by Louis Comfort Tiffany. A smaller Puget Sound scenic window was installed in the sunroom alcove on the west side of the hall. Both windows were removed, and the Burke Museum became steward. The windows, restored, are now on display at the museum on the University of Washington campus.

Loveless Studio Building

711 Broadway E.

Arthur L. Loveless original studio, 1925

Loveless and Fey retail/apartment building, 1930-31

Russian Samovar Restaurant/Cook Weaver

806 E. Roy St.

Steve S. Rodinonoff and V. Shkurkin, designers, 1931

Prolific architect Arthur Loveless designed this charming English cottage-inspired building with ground-level shops and mezzanines that could afford artist studio space, and upper-story apartments arranged around an open interior courtyard. The Russian Samovar (now Cook Weaver) was an original tenant in 1931. Mrs. Larissa Voitakhoff prepared and served traditional Russian recipes brought from her birthplace. She and her husband, P. Voitakhoff, a director for the Russian-Asia Bank, commissioned wall paintings by V. Shkurkin that were partially designed by Larissa Voitakhoff’s son, Steve S. Rodinonoff, who studied architecture in Russia and practiced design. The paintings completely covering the walls of the main and private dining rooms are modeled after the life of Czar Saltan, who reigned in 1200 A.D., as told by A.S. Pushkin. The murals tell the story of a czar, three sisters and a swan-turned-princess.

Art Institute of Seattle/Seattle Art Museum/Seattle Asian Art Museum

1400 E. Prospect St.

Bebb & Gould, 1931-33

This “art moderne” art museum was constructed to the designs of Bebb & Gould to replace a band pavilion in Volunteer Park. The sandstone-faced building was a progressive departure from the traditional Beaux Arts-styled art museums being built throughout America in the first quarter of the 20th century and was especially avant-garde for Seattle.

Queen Anne

Queen Anne Boulevard Willcox Walls

Seventh and Eighth avenues West at West Highland Drive

Willcox and Sayward, 1913 (Walter R.B. Willcox, principal architect)

As public utility projects go, it doesn’t get much better than the wonderful interplay of texture and materials of the tapestry brick and concrete retaining wall and graceful stairways and cast metal lighting standards on the west side of Queen Anne Boulevard designed by Walter Willcox, who later went on to found the School of Architecture at the University of Oregon. Willcox also was the architect of the Arboretum Aqueduct and other fine examples of civic design.

University District

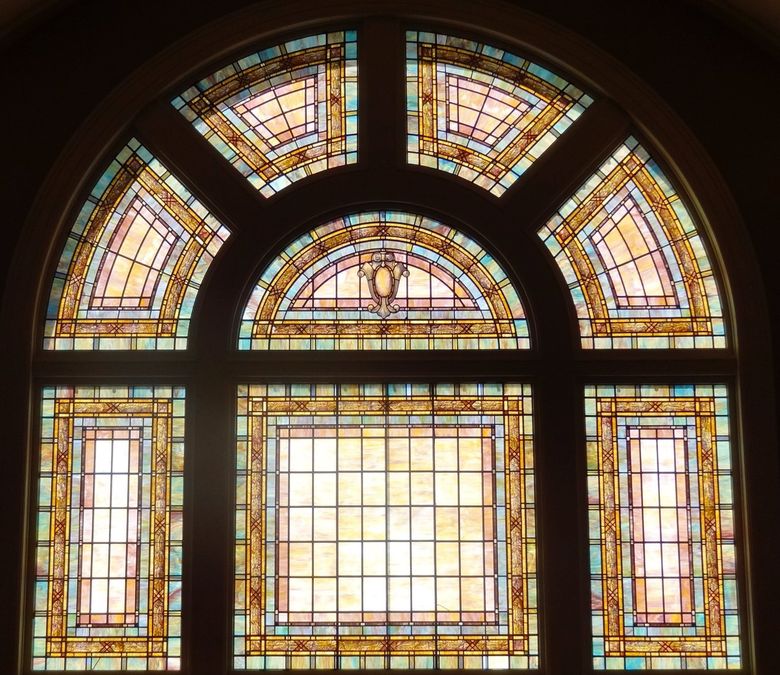

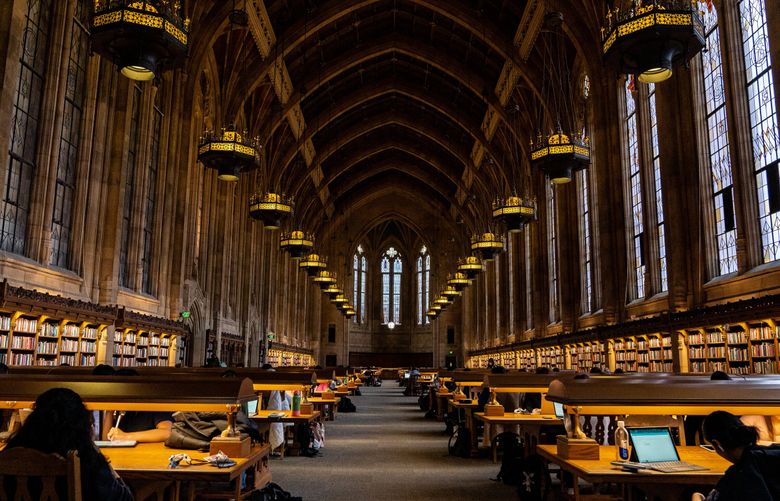

Suzzallo Library

University of Washington

Bebb and Gould, 1924

Local stained-glass expert Raymond Nyson is credited with the main and Smith reading room leaded glass of this superb Gothic Revival space. A 1927 article in The Pacific Builder and Engineer stated, “This room has been pronounced by experts to be the most beautiful on the continent and is ranked among the most beautiful in the world.”