My summer reading list this year included a debut novel by Seth Fried titled The Municipalists, which CityLab described as “the urban planning Sci-Fi novel you’ve been waiting for.” There are many things to say about this novel, but rather than offer a pseudo-review (other than to say that I recommend it), I want to focus on an observation the novel makes about cities. It appears at the opening of the third chapter in the voice of an omniscient narrator that often intrudes on the buddy-cop action to comment on larger themes and ideas. In this case, the narrator tells the reader a truth about cities, a truth which, as I see it, doesn’t get expressed or examined by planners, policy makers, or residents enough:

Many cities impress and please us because they are such perfect examples of human order. Here one thinks of the great European capitals, the streets of Paris lined with orderly rows of five-story Haussmanns or the open-air museum of Rome, where it feels as if not one building has been erected without first considering the argument of the city as a whole […] that everything there is in fact the product of a single unified thought, a calm and artful expression of humankind’s mastery over its environment.

As a person who studies rhetoric in a professional capacity, I’m attuned to how arguments are made and presented, especially in and through urban public spaces. Thus, this observation––that cities are able to make arguments––intrigues me. Most of us, I think, sense this is true. Spending any amount of time in a city––as a tourist, a short-term visitor, or simply on route to some place else, gives us impressions about the city. These visits let us leave with impressions about the city: is it easy to navigate? Is it clean? Does it seem fun? Is it set up for tourists or does it emphasize the resident’s experience?

This passage from Fried’s novel got me thinking: what sort of argument does Tacoma make––about itself and about the people who live, work, and play here? As much as I think about the arguments made by and through urban spaces in a professional capacity, the idea that Tacoma has been configured and organized in ways that impact livability is a personal one for me given my move to the city a year ago. Admittedly, this is a question that can’t be answered easily––and certainly not in the span of a year. No less, it’s a question worth asking routinely, by leaders and residents alike.

In The Municipalists a specific government agency exists to ask precisely this question of cities in the U.S. The central conflict of the novel is derived from differing opinions about how to best pose this question, and by what means to cajole local authorities towards reforms that add up to some sense of “unified thought” over how cities are built and managed. In a sense, the “the politics of urban space” (to borrow a phrase from political scientist Oliver Wiliams) infiltrate the very agency created to mitigate these rationally and empirically.

The U.S. Municipal Survey, as the agency is called, is undone from within because there’s disagreement over what it is cities do best and how best to support them in doing it. What a rogue element in the agency determines is that, in this modern moment, what cities do best is innovate ways of “excluding the poor,” notes Christine Ro of CityLab. This is a determination that too neatly extends beyond the plot of Fried’s novel and into the real world.

But it’s on purpose: Fried is taking a jab at actually existing cities as we know them now, namely San Francisco, New York, and Seattle, for how they’ve remade themselves into places where only the wealthy can thrive, and where there isn’t a place or a way for people living in poverty. In the novel, these reorientations are the result of planning and policymaking that too often appears as progressive, but in effect acts against access and inclusion.

As Tacoma continues to grow, it’s worth considering whether its current and future development will present us as city that welcomes and supports people of varying socio-economic status, or whether it will organize itself in such a way that only those who command six figures or are registered as corporate entities benefit from calling this city home. If recent housing market trends are to be believed, Tacoma is already having to present some sort of answer to this question. Access to affordable housing grows scarcer and the median price of homes continues to increase. People continue to arrive in Tacoma, either because they’ve been displaced elsewhere, or because there’s opportunity and desire independent of what may or may not be happening in Seattle.

To date, Tacoma has made an argument about itself that has contributed to its ongoing growth and development. It is relatively affordable; it is walkable and becoming more so; public transit is good and getting better; there is an abundance of quality parks and green spaces; jobs and economic opportunity exists across a variety of sectors; and civic leaders and residents seem aligned in their vision for the city. And yet: the lesson of The Municipalists shouldn’t be lost on Tacoma: the forces that undo cities come into play when people who live in and lead cities aren’t deliberate about how development is to happen, and about whom benefits from it.

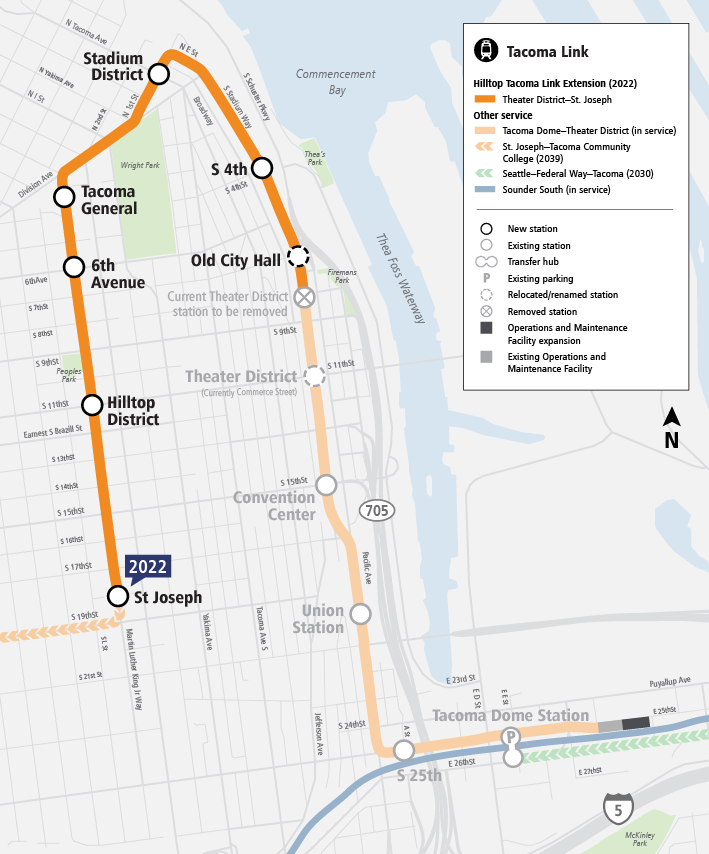

An example: The expansion of Tacoma Link is progressing. On the one hand, an expanded transit system and network (including here the eventual arrival of BRT and Link Light Rail) does improve access and mobility throughout the city and region; at the same time, certain modes of transit, including light rail, have been linked to displacement and to the transformation of neighborhoods that aren’t always desired by long-time residents (see Edward Soja’s analysis of debates had between the Los Angeles Bus Riders Union and the City of Los Angeles’ Metropolitan Transit Authority in 1996).

Leaders in Tacoma have been transparent about their desire to provoke and support economic development along the Tacoma Link corridor. At the same time, community groups and individuals have raised concerns about how this economic development will also contribute to processes of displacement already at work in neighborhoods such as Hilltop. There’s no doubt that people who find themselves priced out of nearby markets will seek out housing in desirable and more affordable areas, especially if these areas are served by regional transit that ensures they just have to switch zipcodes, not jobs. People have a right to move, sure; but longtime residents of neighborhoods also have a right to stay in place.

Then there is development in parts of the city that were not erected with equitable mobility in mind. Point Ruston is an example. This is a collection of market-rate apartments, condominiums, shopping, and dining. Currently, the only way to access the development is by car. Given its location on the Foss Waterway, a long, narrow two-lane road bordered by rail lines on one side and the Sound on the other, it’s hard to imagine how a bus line might allow residents, shoppers, and diners without impacting increases levels of car traffic during the morning and evening commute and on weekends. If transit wasn’t a priority when this area was starting to redevelop, it ought to be now.

Another instance of areas of the city experiencing tensions as a result of growth is the Proctor neighborhood. As the area continues to see development in the form of multi-story mixed-use development, local residents have taken to social media to decry the changing nature of the neighborhood and concerns over parking. And this is a neighborhood that is served by Pierce Transit routes 11, 13, and 16. Will three bus routes be enough in the years to come if this neighborhood continues to attract residents, shoppers, and diners at current rates?

There’s been productive conversations about these developments and future ones this past year. I’ve seen Council members, residents, and civic leaders take up difficult questions, many of which don’t have easy answers. But there is increased awareness and a desire to ensure that the city’s growth and development benefits those who are here and want to stay while also welcoming newcomers. One possible way forward is through transit-oriented development. This approach to development calls upon partners across municipalities and communities to work together to foster urban growth than ensures residents have easy (walking-distance) access to quality transit. (Experiments in San Francisco and New York City have shown that this type of deliberate growth does help address disparities that result from more traditional development.)

Transit-oriented development does require the buy-in of city officials, developers, and transit agencies, which isn’t always easy to attain. But Tacoma has signaled it’s willing to do the work, having constituted the state’s first Transit-oriented Development Advisory Group on August 19.

Tacoma is in the process of crafting a new argument about itself as it grows into a different place than it is and has been. In part, we are having to craft this new argument because of the success of a previous argument. In many ways, Tacoma has made itself into a welcoming and livable city where people from all sorts of places and backgrounds can participate in the making of a city that, by and large, seems like the “product of a single unified thought, a calm and artful expression of humankind’s mastery over its environment.”

This is an argument that has been hard-fought: Tacoma has its own histories of dramatic exclusions ranging from the expulsion and murder of Chinese people in 1885, to the racist real estate practice known as “redlining” that was practiced widely in the 1950s and 1960s, and which helps explain some of Tacoma’s geographic makeup today. Whether or not Tacoma will become a city that continues to organize itself in ways that foster livability, access, and equity, or whether it will allow itself to become exclusionary in the way other cities have––that’s a determination we can start making today.

Whatever argument Tacoma makes regarding the type of city it is and about who it welcomes and excludes is an argument that is derived and presented collaboratively. In fact, there can be no “product of a single unified thought” when it comes to cities, nor should there be. What cities do best is foster the conditions through which people who differ in all sorts of ways––including opinions as to how one should live––can work together to create the spaces and places in which we can all prosper. Cities, I would argue, are the utmost rhetorical project: each and every one is a new and novel experiment in how people who have little in common remake themselves into a group of people working towards a common purpose.

Toni Morrison, who died this month, held similar thoughts about the potential of––and inherent in––cities. In her novel Jazz, she writes this about Harlem:

Do what you please in the City; it is there to back and frame you no matter what you do. And what goes on on its blocks and lots and side streets is anything the strong can think of and the weak will admire. All you have to do is heed the design–the way it’s laid out for you, considerate, mindful of where you want to go and what you might need tomorrow.

The common purpose Tacomans will see through in the next so many years is currently being defined. It’s on all of us to consider what argument our city will make about itself and about us once we’ve decided. Ideally, it will be the type of city that will “frame us” no matter what we do, a city whose blocks and lots and side streets are laid out to back us in whatever ways we seek success. A city deliberately designed for inclusion, access, and justice.

Rubén Casas

Rubén joined The Urbanist’s board in 2022. He is a scholar and teacher of rhetoric and writing at the University of Washington Tacoma. He is also the faculty lead of the Urban Environmental Justice Initiative at Urban@UW. In his work and advocacy, Rubén examines how cities and the institutions that comprise them imagine, plan, and build in ways that promote and/or discourage community and a sense of place.