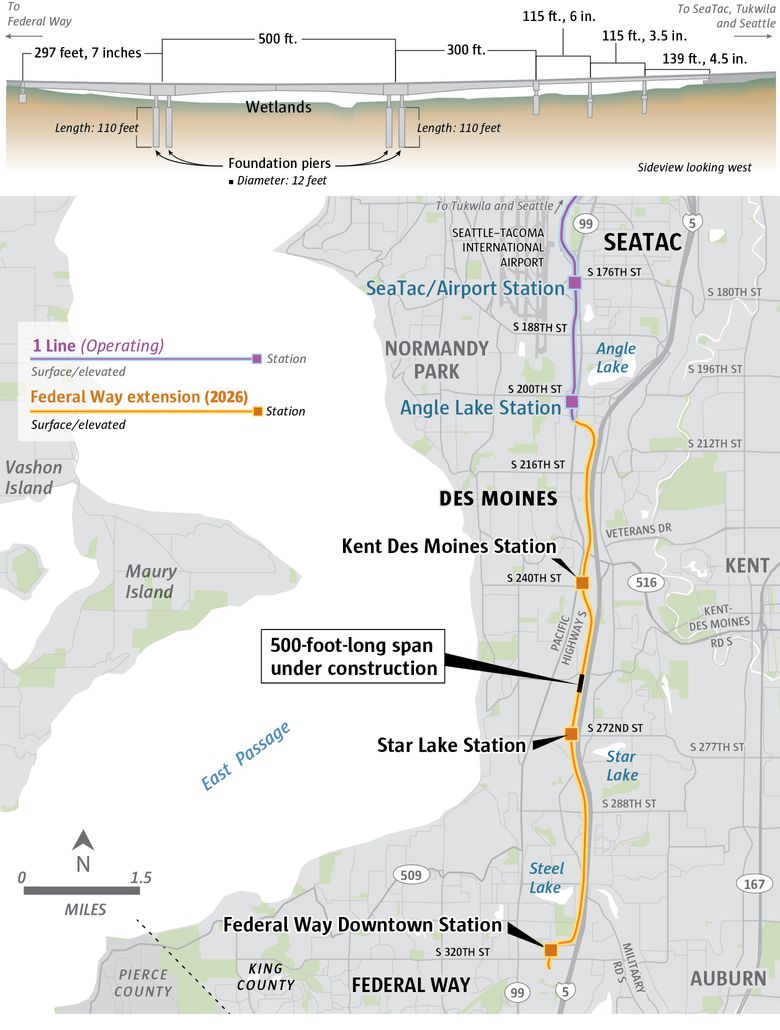

KENT — Millions of travelers have glimpsed a huge Sound Transit bridge taking shape along Interstate 5, where light rail trains will sometimes outrun freeway traffic jams, and sometimes get passed, when service begins in 2026.

After years of anticipation, the progress is more rapid and visible as construction workers form the decks. Yellow frames and cranes shine by day, while security lights shine by night, here at the doorstep of Federal Way.

Contractors will soon pump a final load of concrete to close the final 9½-foot gap in the center, where north and south girders lunge toward midair.

This is the longest bridge in Sound Transit’s system, and it represents the most difficult part of the $3.2 billion light rail, 8-mile extension from Angle Lake to downtown Federal Way.

Voters were promised light rail service by this year until Sound Transit learned the soil was weaker than early route designers realized. It took three tries for the agency and contractor Kiewit Infrastructure West to produce a shape whose 500-foot-long central span passes over wetlands instead of through them, while withstanding a massive future earthquake. Kiewit expects to complete it by September.

“Thank goodness they solved this soil instability before it became a problem after construction,” Federal Way Mayor Jim Ferrell said. He considers the timing neither too early nor too late, but just right, as the city of 102,000 redevelops its traffic-riddled downtown.

Transit enthusiasts might call this place South King County’s version of the Golden Spike, driven in 1869 when continental railroad tracks converged in Utah Territory.

Nearly all the other components, such as tracks, ballast gravel and parking, are done, paving the way for the Kent Des Moines, Star Lake and Federal Way Downtown stations to open by 2026 without further delays.

Federal Way Link is projected to attract 18,000 to 23,000 daily passengers, especially people who work or travel at Seattle-Tacoma International Airport, spokesperson David Jackson said.

After all four new lines to Lynnwood, downtown Redmond, across Lake Washington, and to Federal Way are finished in 2024-26, light rail should carry 156,000 to 203,000 daily passengers by 2028, according to new figures from Sound Transit. That’s lower than previously advertised targets, but similar to daily counts of I-5 vehicles at Federal Way.

Finding a quagmire

The new bridge sits within Kent city limits south of Midway Landfill, on a hilltop bordering McSorley Creek wetland. Rainwater collects in the wetlands before trickling 2¼ miles into Puget Sound, at Saltwater State Park.

Way back in 2008, voters passed the Sound Transit 2 sales tax increase, whose campaign maps depicted a train line to the Star Lake Park-and-Ride in north Federal Way. But the project was postponed by the lull in sales tax revenues that accompanied the Great Recession. The ST3 tax vote in 2016 brought new money and a new promise, to reach downtown Federal Way by 2024.

The project encountered a quagmire.

Its critical crossing midroute was supposed to be a basic bridge, with columns close together, between two small hills where tracks sit on the surface. But in November 2020, Kiewit sent notice that the soil was weaker than portrayed in Sound Transit’s geotechnical study, according to a transit staff report.

Sound Transit agreed that because of potential soil liquefaction, the columns might not withstand a maximum “2,500-year event” earthquake, also defined as a 4% chance of happening per century.

That means a bridge is supposed to outlast all possible quakes, said Jeffrey Berman, University of Washington engineering professor: a repeat of the Cascadia Subduction Zone quake and tsunami of 1700, about 9.0 magnitude, off the Pacific Coast; another Seattle Fault quake of 930 A.D., which triggered a Puget Sound tsunami and lifted hillsides 10 feet; or a more powerful version of the deep Nisqually quake of 2001. Though far offshore, a subduction quake would likely inflict more damage, Berman said, by generating “long period” underground waves up to 2 seconds apart, so the ground oscillates with accumulating intensity.

A 2,500-year standard assures that following a lesser quake, mass transit can restart quickly, without catastrophic interruptions or repair bills, according to the Link design requirements manual.

Project leaders altered the design to prescribe deep and rigid columns, topped by seismic bearings that would let the bridge deck slide slightly.

But they stepped on the brakes in July 2022, when a mudslide briefly closed a lane of I-5 just feet away. Engineers realized the very act of digging and filling multiple column holes would further weaken the hillside, said Sepehr Sobhani, deputy executive project director. Kiewit answered with a third version, a behemoth resting upon two sets of twin piers 110 feet deep, where they’re anchored in hardy glacial soil.

Why didn’t Sound Transit discover these risks a decade ago, by taking more soil samples?

“In hindsight, it would have been a great investment to do more boring,” Sobhani answered. “Before it was cleared out, you had a highly vegetated, somewhat steep slope of trees and you were pinched between the freeway and the wetlands. So it wasn’t the best area to go in there and just clear out a big road and take a bunch of borings. We were able to get in there and get, like, one boring [for] the preliminary design.”

Since taking over final design, Kiewit says it took 29 soil samples.

A balancing act

The bridge is what’s known as a cast-in-place balanced cantilever bridge, similar to the 1984 high-rise West Seattle Bridge. Concrete masons and ironworkers begin at each giant pier, then extend the decks outward at a similar pace, maintaining a balanced T-shape when viewed from ground level.

The force of gravity, which wants to pull the bridge down, is redirected back toward the heavy piers, both by the partially arched girder shape, and by 103 miles of steel internal cables, which compress the bridge lengthwise to up to 1.05 million pounds of force, a method called post-tensioning. (Imagine holding two soup cans outward at shoulder height, as your arms and core muscles tighten.)

Each new segment is cinched to the whole girder by new sets of steel post-tension cable, threaded through plastic conduits in girder walls. Those cables are unspooled from a round cage, parked on the unfinished bridge deck, that looks like an overgrown drain-cleaning snake.

Each new segment lengthened the bridge 7 feet to 15 feet. Elevation errors of up to a half-inch are endemic and require frequent fine-tuning. “Every segment has minor adjustments to meet our target,” said Sound Transit construction manager Mike Jellison. “Our contractors are doing a great job of executing the work.” Besides the final pour in the middle, there are two gaps to fill at the side spans.

If needed, workers can align these critical parts using beams and jacks, according to Ian McPherran, a Kiewit construction manager.

As the concrete hardens, it heats through chemical reaction. Kiewit planted water-filled tubes within the walls, so water can temporarily circulate as in a power plant cooling tower. Otherwise, the mix could exceed 160 degrees as it cures, McPherran said.

The Federal Way line includes movable forms previously used in Portland TriMet’s Tillikum Crossing, he said.

Steel-framed gantries scoot forward on I-beams, anchored temporarily into the bridge deck. They lift and move the tub-shaped molds ahead. Gantries leave in their wake hundreds of anchor holes, which workers filled with miniature soccer balls, baseballs and basketballs, to be patched later.

Similar devices were deployed to form a light rail overpass at Interstate 90 from South Bellevue to Mercer Island, where the 2 Line to Seattle should open by winter 2025-26.

Years ago, an overhead gantry hoisted 2,457 hollow concrete pieces over Tukwila, for the initial light line that opened mid-2009. Workers didn’t need to plop cranes, bridge piers or temporary scaffolds in the Duwamish River.

In the same way, the Federal Way Link project will avoid the soft and narrow ground bordering McSorley wetland, said Sobhani. The central span sits 10 feet to 30 feet above the uneven ground.

For extra protection, Kiewit surrounded the tops of bridge piers with rings of concrete cylinders 35½ feet deep, a shield against mudslides during construction. Those resemble the huge ring Seattle Tunnel Partners built in 2014 to help excavate and retrofit Bertha, the stalled Highway 99 tunnel boring machine.

Taxpayers will foot the bill for the extra effort.

Sound Transit’s governing board agreed in May 2023 to pay Kiewit $109.8 million for bridge changes and smaller items, boosting the total corridor contract to $1.64 billion.

Such payouts happen frequently in megaprojects. Typically, government sponsors like Sound Transit or the Washington State Department of Transportation do the soil research and “own the ground,” so to speak. Otherwise, companies would submit exorbitant bid prices to reduce their risk. Therefore, the public is on the hook for underground surprises, like sewer pipes blocking streetcar power pole foundations in Tacoma.

Cantilever fever

About 450 road bridges and 50 transit bridges in the U.S. have been built in a similar way since 1973, according to the American Segmental Bridge Institute.

Some in Washington include the I-90 westbound crossing of Denny Creek near Snoqualmie Pass, the Highway 509 Thea Foss Waterway bridge in Tacoma, Interstate 182 in Richland over the Columbia River, and Interstate 205 over the Columbia between Vancouver and Portland.

Sound Transit’s 500-foot-long mainspan, the centerpiece of its 1,100-foot bridge known as “Structure C,” is longer than most, but these types can stretch 800 feet before overhead cables become necessary, said Gregg Freeby, the institute’s executive director.

“The great thing about Structure C is that it’s not particularly novel to the bridge community,” Freeby said in an email. He called it an example of solving a problem, namely that poor access forced a decision to build gantries and forms away from the ground. “That’s where concrete segmental shines — construction from above.”

100-year trackway

Federal Way Mayor Ferrell said he’s OK with the prolonged construction, just as he’s not outraged when his airline flight is delayed for safety reasons, and that Sound Transit’s communication has been stellar.

“The stars are aligning for Federal Way,” Ferrell said.

Ferrell said his city is eager to host celebrations and traveling fans during six World Cup soccer matches in Seattle beginning June 15, 2026. A simple walk-bike bridge to the station, over a slight dip in busy South 320th Street, looks buildable before light rail arrives, city staff said.

Later that year, a master-planned neighborhood called Town Center 3 will add 900 housing units, a plaza, offices and retail to 500 existing homes around the station, followed by proposed redevelopment of The Commons at Federal Way mall to bring more housing, parkland and a new road grid. The city’s growth target is 5,000 units downtown in a couple decades.

“Take your time,” Ferrell said. “Sound Transit is building hundred-year infrastructure, so we need them to get it right.”

Or if the Earth’s crust cooperates, a 2,500-year structure.