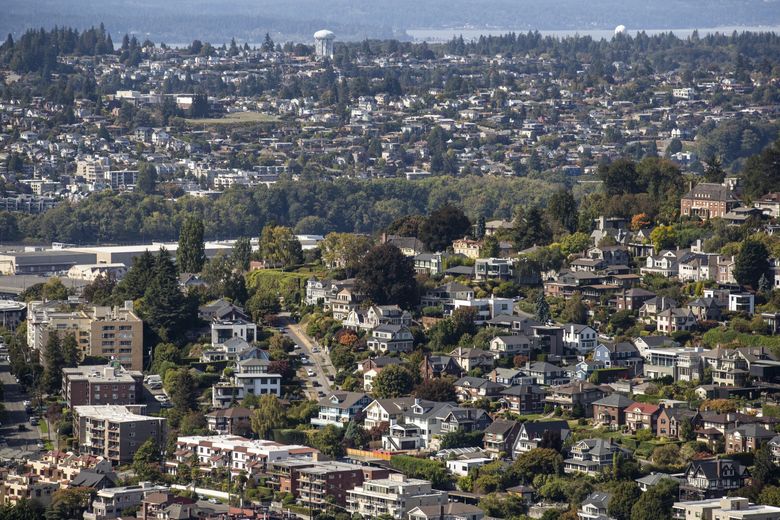

This may be the year of aggressive efforts to increase the housing supply in Washington and Seattle.

A total of 13 bills are moving through the Legislature with bipartisan support. They would speed permitting, make it easier to build “mother-in-law” units adjacent to existing houses, and allow lots of more than 1,500 square feet to be subdivided to allow for more building.

According to a poll commissioned by the Sightline Institute, which favors more density, 71% of respondents supported a proposal to eliminate local zoning ordinances that allow exclusively single-family housing in localities with more than 6,000 residents. The caveat: The sampling was only 613 voters.

Not all proposals are sure to pass without a fight. For example, House Bill 1110 is moving slowly through the process in Olympia.

It would override local zoning rules in cities statewide to allow for greater density in every neighborhood and end exclusive carve-outs for single-family houses. Not surprisingly, this is facing opposition from localities seeking to retain control of zoning and residents concerned about preserving neighborhood character and property values.

Oregon passed a law to eliminate single-family zoning for localities of 10,000 or more in 2019. California passed two measures in 2021 doing much the same thing. Minneapolis was the first major city to take this step, in 2019.

Another controversial set of bills concerns landlords and tenants. They would put a cap on rent increases and require additional advance notice of large rent hikes, among other new regulations. For example, House Bill 1388 isn’t shy about its intentions: “Protecting tenants by prohibiting predatory residential rent practices and by applying the consumer protection act to the residential landlord-tenant act and the manufactured/mobile home landlord-tenant act.”

Landlords are opposed to this and other measures and not out of venality. Unintended consequences abound, such as mom-and-pop landlords carrying mortgages might be forced to sell. The rental property would be taken off the market as McMansions are built in their place.

Paula Joneli of Des Moines recently wrote a letter to the editor arguing, “As we contemplate introducing multifamily zoning into ‘traditional’ neighborhoods, perhaps we also need to consider limiting non-owner occupancy rates in residential neighborhoods.

“Non-owner occupants typically hold properties for income and appreciation while living away from the property. Absentee owners contribute to neighborhood declines. ‘Buy and hold’ strategies decrease sellable homes, resulting in price increases/seller profits, with the end result of less affordable homes. Note: Limiting NOOs does not preclude an owner from living in one unit of a two-, three- or four-Plex as their primary residence.”

Yet a differentiation should be made between private equity and other financial outfits owning large numbers of properties as investments, and ordinary landlords who live off the rents on one or two houses. No evidence exists that the latter always contribute to the decline of neighborhoods. Aside from the stereotypical slumlord, these owners have a vested interest in maintaining quality neighborhoods.

Still, the goals of the legislation are to increase housing supply and make it more affordable.

Nationally, the median home price was $427,500 as of January, according to the Census Bureau and U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development. Washington’s was $560,400 as of 2021, according to the most recent state data.

The University of Washington’s Washington Center for Real Estate Research pegged the median resale value of a house in King County at $860,100 in the fourth quarter of 2022. Meanwhile, Zillow recently reported the average house “value” statewide was $553,846, up 3.9% over the past year.

However you slice it, Washington — and especially the Seattle area — is one of the most expensive areas to live in the country.

At the same time, the state Department of Commerce estimates Washington will need 1 million additional dwelling units by 2044.

Meanwhile, Seattle voters recently approved a measure to create so-called social housing.

The novel — at least in the United States — program creates a quasi-governmental social housing developer to build or convert, as well as manage, low-income housing in the city. The units would cater to people making between 0% and 120% of the area’s median income. Rent would be capped at no more than 30% of their income.

The catch is where the funding would come from. It’s not included in the city budget — already stressed by the consequences of the pandemic — and help from the state and federal government isn’t guaranteed. New taxes would be sure to cause a brawl in Olympia.

And this would be on top of the Seattle Housing Levy, which funds projects for the lowest-income residents. Voters will be asked to renew it in November at an estimated $900 million.

It’s worth noting that more affordable housing is already available in the region, at least as so-called “workforce housing” for teachers, police officers, firefighters and other middle-income residents.

This ranges from increasing transit-oriented development along light rail, to locations in Tacoma and elsewhere in Pierce County. Sound Transit could help by rearranging schedules for Sounder commuter trains from traditional office hours to trains throughout the day and at night.

But all these new measures pose the ultimate question of whether the most desirable West Coast cities can be made genuinely affordable.

As a young reporter in the 1980s, I covered real estate in San Diego. Paid in “sunshine dollars,” I could barely afford my apartment two blocks from the beach and had no hope of ever buying a home. I had to set out and continue my career elsewhere, gaining skills and experience, and earning better salaries until I could.

And San Diego? It’s as expensive as ever, with marginal ups and downs. The same is true for Seattle.

We’ll see what happens now.