Article Summary:

By

SOMETIMES THE MOST intriguing things arrive in very plain packages.

Take, for example, one overcast, workaday Wednesday several weeks ago, when a few high-ranking executives from Seattle City Light strolled into City Hall to give a presentation.

Everything about the situation defied excitement: the hour (midweek, 10 a.m.), the venue (a city council committee), that committee’s mood (subdued and a little distracted, with one telecommuting council member murmuring, perhaps to herself, on a hot mic), even the title of the slide deck City Light officials brought with them (“Western Markets Energy Briefing”).

Not exactly the recipe for a thrill ride.

THE BACKSTORY

From its origins to its consumers, electricity is a powerful social force

But the executives, led by Jim Baggs (City Light’s regulation and market development officer) and Debra Smith (its CEO), seemed improbably chipper. Enthusiastic, even.

They hadn’t come to ask the council for anything — not yet. But soon, they explained, they might return, seeking approval to join two large, multistate initiatives with impenetrable names. One would be an energy-planning and energy-sharing agreement called the Western Resource Adequacy Program (or WRAP, based in Oregon). The other would be one of several energy-trading markets currently under construction — though the front-runner seems to be something called the Extended Day Ahead Market (or EDAM, based in California).

But first, before anybody could possibly understand what any of that meant — or why it was important — the officials had to explain a few things.

Like tenured English professors whose fire for poetry cannot be dimmed by even the sleepiest students, Baggs and Smith taught the room a lesson in our corner of the electrical grid — how it works, its kaleidoscopic connection with every other corner of the grid, the troubling energy shortages on the horizon — with zeal.

“That’s a lot of energy gibberish that makes a lot of sense to us utility geeks, but it’s really critical,” Baggs interjected at one point. “Because what we’re doing here is talking about fundamentally changing the manner in which decisions are made and how operations are carried out.”

In other words: Listen up. Big changes might be coming to a light switch near you.

The big picture

At its core, this is a story about climate change and averting catastrophe — but it might not be the kind of climate-change story you’ve come to expect.

It’s not about cinematic disaster: wildfires, storms, droughts. Not about how Antarctic sea ice hit a record low in February, or the fact that unprecedented monsoon rains left one-third of Pakistan underwater for a few weeks last summer. Or how, thanks to us, the level of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere is higher than it’s been for at least 800,000 — and maybe even 3 million — years.

Though it wouldn’t hurt to keep all that in mind.

It’s a story about electricity, and how utilities and other power players (locally and interstate, together) are cooking up plans to decarbonize the grid — one of the top greenhouse-gas emitters in the United States.

The problem, in a nutshell: How do we replace steady, predictable fossil fuels (coal, natural gas) with less predictable resources (wind, solar) in a moment when so many other variables (climate, weather, technology, consumer behavior) are also in flux?

And how do we keep “greening” the grid while maintaining reliable power — without running into dire, potentially lethal, energy crises like the ones we’ve recently watched in Texas and California?

It’s a puzzle.

Lights out?

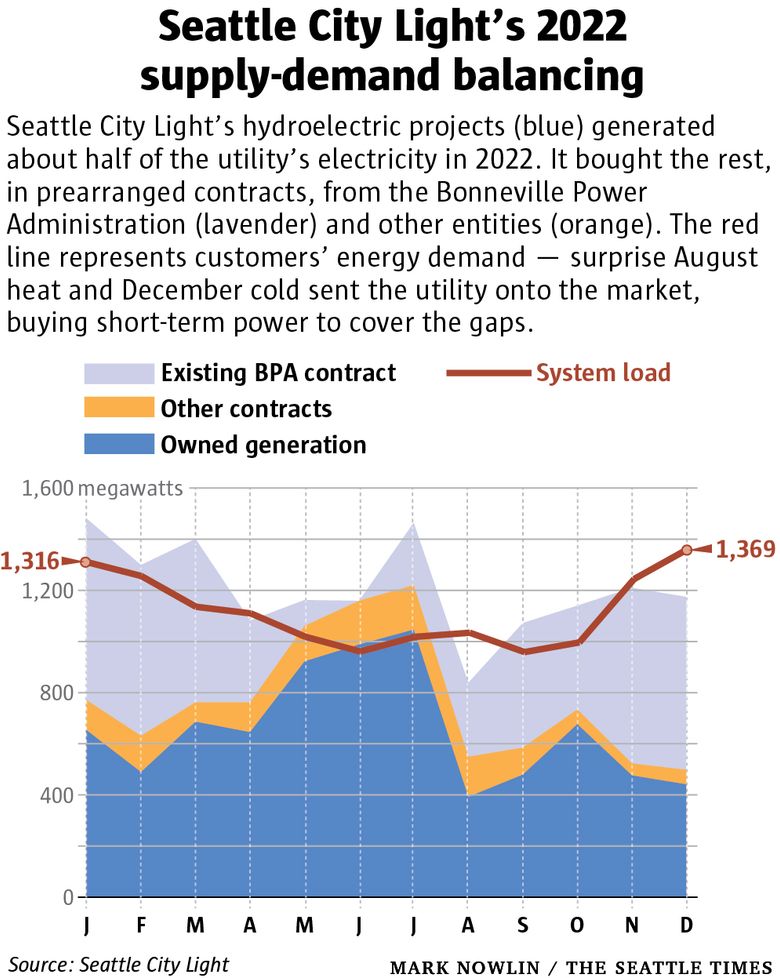

Several recent, major studies have sounded ominous warnings about that challenge, projecting possible energy shortages in the thousands of megawatts. (That’s no small shortage. In 2022, Seattle City Light was meeting an average “load” — or demand — of 1,121 megawatts at any given time. For context, a single megawatt could simultaneously power 400 to 900 homes, depending on the time of year, etc.)

“You’ll find a range of deficit estimates, depending on who you talk to,” says Emeka Anyanwu, an electrical engineer by training and now the quick-talking, no-nonsense innovation and resources officer at Seattle City Light. “What isn’t in dispute is that we are looking at deficits — in Washington state, regionally and nationally — in the energy we’ll have versus the energy we’ll need.”

Or, as the Western Electricity Coordinating Council (WECC, one of the authorities in charge of the grid west of the Rocky Mountains) put it more alarmingly in an oft-cited 2022 report: “If nothing is done to mitigate the long-term risks within the Western Interconnection, by 2025, we anticipate severe risks to the reliability and security of the interconnection.” (The Western Interconnection is the portion of the U.S. grid west of the Rocky Mountains.)

City Light says the two initiatives under consideration — the WRAP, an energy planning-and-sharing agreement, and EDAM, a marketplace — both attempt to address those risks. In order to overhaul our energy infrastructure (out with the dirty, in with the clean), we’ll have to adjust the way we behave on that infrastructure.

If the grid is a nightclub with a decrepit floor, we don’t just need to upgrade the hardwood — we need to change the way we dance.

Grid basics

To understand why, we have to understand the scope of the problem.

Most Read Stories

- Seattle-area millennials are buying homes — just not in King County

- School closures, cuts to clubs and music possible as WA schools face ‘cliff’

- The Cold War between WA and neighbor Idaho gets hotter

- Unlike other airlines, FAA won’t let Horizon fly without anti-collision system

- Montana House speaker silences trans lawmaker for 2nd day

The U.S. electric power sector is the second-largest greenhouse-gas emitter in the country, exhaling around 33% of our nation’s carbon dioxide.

First place goes to transportation, which we need to electrify — along with everything else — if we’re going to help avert the worst of the climate crisis.

To make transportation truly green, we need a green grid. Again: To have a green grid, we need to lean less on predictable, steady sources of fuel (coal, natural gas) and more on variable resources (wind, solar).

Unfortunately, “variable” also means “unreliable.” If you need more power from a coal plant, just shovel some cinders. If you need more power from the solar farm, but clouds — or wildfire smoke — just darkened the sky, you’re kind of screwed. You’ll need to draw power from somewhere else.

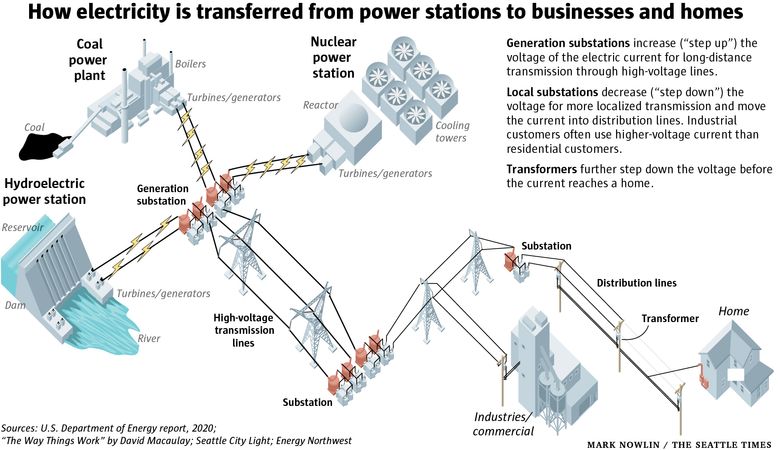

Generating solar and wind power, then storing it in grid-scale batteries for later, is a holy grail — but we’re not quite there yet. Which leads to a complication: The physics of the current grid, which are utterly nonnegotiable, demand that power is generated at the same moment it’s used. Unlike rice or cushions or clarinets, you can’t box up surplus electricity for later.

“If you live in hydro country,” writes anthropologist and grid scholar Gretchen Bakke, “the electricity you are using right now was, about a second ago, a drop of water.”

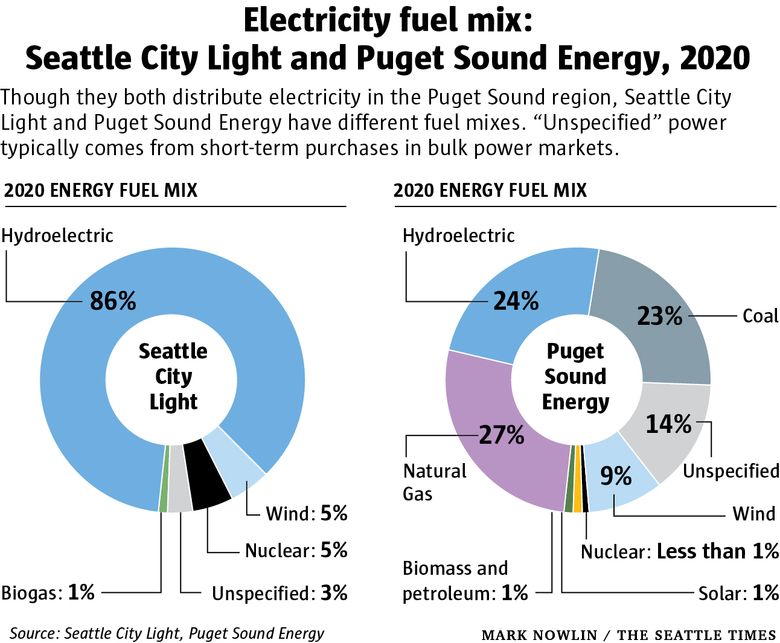

That’s a slight oversimplification — Seattle City Light uses 80% to 90% hydro; Puget Sound Energy uses around a quarter, and also leans heavily on natural gas and coal, making it the state’s largest greenhouse-gas emitter — but you get the idea.

All your kilowatts are fresh. Fresh as lightning.

The social machine

Because we live in “hydro country,” electricity users in the Pacific Northwest might know that our region is relatively decarbonized already. (In 2022, hydropower churned out just 6.2% of U.S. electricity; Washington dams usually generate between a fifth and a third of that 6.2%. Those dams — which have destroyed Native settlements and interrupted salmon runs — also remain a source of anger and controversy. State, tribal and federal leaders continue to debate which, if any, should be removed.)

But the grid is a deeply interconnected, deeply social machine.

In the continental United States, the grid is broken into three main zones: Western, Eastern and Texas. Which means that, west of the Rockies, more than 80 million people in 14 states, plus chunks of Canada and Mexico, belong to one big electric community.

No utility is an island.

As Jim Baggs explained to the city council committee that Wednesday morning: Twenty-four hours a day, seven days a week, people sit at desks swapping megawatts with each other — whether those come from dams on the Columbia River, solar panels in the Oregon Badlands or coal furnaces in Montana. (Yes, even Washington’s greener utilities acquire at least a few megawatts from fossil-fuel plants now and then — sometimes inadvertently, through third parties. State law says they’ll have to quit all coal by the end of 2025 and be greenhouse-gas neutral by 2030.)

Why so much swapping? Because the nonnegotiable grid physics also demand that the system be balanced at all times, matching “resources” (supply) with “load” (demand). If the system has too much energy, things could — in a worst-case scenario — overload, melt and/or break. If the system has too little energy, we’d have blackouts.

The trading happens constantly. It has to.

Much of that trading is in future contracts: what a utility such as Seattle City Light (which generates around 40% to 50% of its electricity from its own hydro projects) thinks it should buy or sell for next month, next week or tomorrow. Sometimes, the trading happens in five- or 15-minute increments. If a surprise cold snap hits Seattle and everyone turns up the heat, creating a sudden spike in load, City Light goes on the market looking to buy megawatts from other energy-producing entities around the West — even if, the day before, it was out on the market selling.

Increasingly erratic weather can trigger increasingly erratic consumer demand. In 2013, the U.S. Census Bureau reported that 31% of Seattle households had air-conditioning (either central or window units). In 2019, that number bumped up to 44.3%. In 2021, it hit 53.4%.

Come the next heat wave, that might add a little strain.

Some efforts to decarbonize the grid will be obvious and alluringly photogenic, landing on the front covers of annual energy-industry reports: solar panels glinting in the desert, offshore wind turbines spinning above the waves.

Other efforts, like the WRAP, and new markets such as EDAM, will be invisible — not what we build but how we behave, and how our utilities interact with each other across this massive social machine.

“Part of greening the system means you want back-and-forth optimization across a wide geographic footprint,” says Anyanwu, of Seattle City Light. “From surplus to need, need to surplus. You want to import solar from California and the desert Southwest, for example, to displace those fossil-fuel resources. It’s greening the mix.”

If we want to decarbonize, it’s going to be a team effort.

How it works: the WRAP

The Northwest Power Pool has been coordinating team efforts since World War II, when it helped lash together different utilities’ systems, providing massive amounts of reliable power for wartime projects: shipyards, aluminum mills for fighter planes, the secret atomic-bomb program at Hanford.

Last year, the organization changed its name to the Western Power Pool (WPP) after it embarked on another ambitious effort: the Western Resource Adequacy Program.

Think of the WRAP as a kind of neighborhood pact, in which each neighbor shows the others it has enough resources to meet its own needs, plus a little extra for anyone in a pinch.

“I use a musical-chairs metaphor,” says Rebecca Sexton, director of reliability programs at WPP. “We want to make sure everybody has enough chairs to sit down during those really hot or cold days — and motivate everybody to bring the right number of chairs to the game.”

For decades, she says, utilities have been making their own assumptions about energy: how much they’ll need, how much extra they should budget for surprises, how much will be out on the markets to buy if they find themselves short.

Now, in an increasingly volatile energy world, WPP argues, that’s an increasingly dangerous approach.

“At some point, you’ll be calling your neighbors for energy, and they won’t have it for you,” Sexton says. “We need to get together and understand what energy is actually out there.”

The program has two prongs. Prong one: the “forward showing” program, in which each utility shows it has enough resources for next winter or summer (the high-demand seasons). Prong two: the “operational program,” in which a utility in trouble can send up a flare and ask for help from the neighbors.

There’s also a third component: enforcement. The charge for noncompliance (failing to bring “the right number of chairs”) can be steep — roughly modeled, Sexton says, on the cost of building a whole new energy resource, then doubling that. (In February, the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission approved the WRAP plan, including its noncompliance charges.)

So far, around 20 utilities — large and small, publicly owned and privately owned, from Nevada to California to Idaho — have joined the early, “voluntary” phase of the WRAP. The “binding” phase, when utilities formally become part of the neighborhood pact, comes between the summers of 2025 and 2028.

This spring, Seattle City Light plans to ask city council for permission to join that binding phase — their Grid 101 presentation at city hall was the warm-up.

How it works: EDAM (and its competitors)

In the old days, the western grid’s day-in, day-out energy trading happened on a bilateral basis: If Utility A needed megawatts, it picked up the phone to call Utility B. If Utility B didn’t have them, it called Utility C. And so on.

That changed in 2014 with the Western Energy Imbalance Market (WEIM), a day-of, real-time energy marketplace designed to automatically find the best value for Utility A’s needs.

If the WRAP tells you how much energy capacity is in the neighborhood, WEIM finds you the bargain megawatts. (Run by the mammoth California Independent System Operator, or CAISO — which manages 80% of that state’s electricity flow — WEIM is separate from the WRAP, though they’re widely seen as complementary.)

“The market picks a resource out of a stack,” says Baggs of Seattle City Light. “Maybe there’s a shortage in Idaho in the next five minutes, and they’ve got a resource nearby — but there’s a different, cheaper resource in Washington. The real-time market allows the cheaper resource to go to Idaho.”

These days, Baggs says, more than 80% of the western grid participates in WEIM. Since joining that market in 2020, City Light reports that WEIM trades have saved customers around $30.7 million.

Trades for tomorrow and beyond are still handled bilaterally. But WEIM has worked so well, CAISO is planning an expansion, from the current day-of market to a day-ahead market: the Extended Day Ahead Market, or EDAM. (Competitors also want a piece of the action, including the Arkansas-based Southwest Power Pool, which is developing a similar product called Markets+.)

EDAM is not nearly as far along as the WRAP. But if it works as hoped, it could mark a major change. Today, Baggs says, maybe 5% of energy in the West is traded on the day-of market (WEIM). The day-ahead market (EDAM) might be trading more like 40% of the energy.

That would, City Light argues, allow us to trade more nimbly — saving money while allowing us to buy and sell more power from the sources we’d like, including wind and solar plants throughout the West.

Questions remain: Might EDAM (which tries to find the best deals) conflict with the WRAP (which asks utilities to plan and hold energy for neighbors)? How would EDAM, in its search for bargain megawatts, make sure Washington utilities aren’t getting fossil-fuel energy after the state’s quit date?

The answer from all corners: We’re working on it. Sexton, with the WRAP, says compatibility between the two projects “is a big focus.” Seattle City Light emphasizes it hasn’t committed to joining EDAM, or any other new market — and that it must, of course, comply with state law.

Critique and hope

Both of these strategies (the markets, the WRAP) are sparking optimism among industry players and independent observers alike — particularly the WRAP, which is closer to realization.

“Pretty consistently, people interested in decarbonization would see the WRAP as a step in the right direction,” says Stephanie Lenhart, a faculty member and senior research associate at Boise State University, who has been studying grid-governance issues for the past 10 years. “Though some people are saying it doesn’t go far enough.”

Some of the not-far-enough crowd, she says, would like to see a full-blown regional transmission organization (RTO), like the ones in the Midwest and Northeast: a more centralized authority that might speed decarbonization. But, Lenhart says, the West has repeatedly tried to organize that kind of thing in the past and always failed — partly because the West is so diverse in its resources, politics, economic priorities and community identities. Agreement is hard to come by.

In contrast, she explains, the WRAP and EDAM allow local control. They don’t tell anyone what resources to use: coal, wind, whatever. They just help everyone better understand what’s out there, and get what they need — though markets such as EDAM might put an economic squeeze on fossil fuels by making renewable resources easier to find.

“They will potentially allow trading of wind and solar over larger regions,” Lenhart says, “which will put cost pressure on other resources.”

Again: No utility is an island. Nor should they be, says Anyanwu, the innovation and resources officer at Seattle City Light.

While decarbonizing means relying less on big fossil-fuel plants, and more on decentralized nodes of variable power, Anyanwu stresses we should continue to value the big grid, in all its complicated interdependence. We shouldn’t get swept away in any provincial, carbon-free-homesteader fantasies. Secession isn’t the answer.

“We have to be super-careful in this transition not to create more inequities,” he says. “If you move into a space where much of the asset investment is in rooftop solar, for example, or localized batteries, you run the risk of developing a tiered energy system — solar on the roof and a Tesla in the garage for some, and a disinvested energy grid for everybody else.”

The big grid, and big-grid solutions, he argues, is still the best way toward decarbonization — and energy justice.

Sometimes the back-end details sound, as Baggs put it to the city council committee, like “a lot of energy gibberish.” But the stakes are real — and high.

“This is a good evolution, a practical evolution, a hopeful evolution,” Anyanwu says. “It’s a mechanism by which we help respond to the climate crisis.”