Jason Wood and his wife left Sacramento, Calif., for Seattle three years ago. The couple — a pair of veterinarians with two cats and two dogs — had been considering a change of scenery. When a new job opportunity arose, they decided it was the perfect time to go. During the transition, Wood invited his best friend to join them on the journey.

“He’s kind of like a brother to me,” Wood, 42, recalled. “We said, ‘We’re moving. Do you want to come with us?’”

His friend was initially on board — then came the reality of the Seattle rental market. “It’s too expensive here,” Wood said. “With how much money he makes, he cannot afford anything in this city.”

So, Wood and his wife took out a home-equity loan on their new house in Columbia City and built a detached backyard cottage for their friend to eventually live in.

What they did isn’t exactly unusual. In Seattle and beyond, more people have found that the best place to expand housing options for themselves or others is right in their own backyards.

The single-story structure, completed last year, measures 340 square feet and it is basically a “studio-style apartment.” Wood charges his friend $675 a month in rent, which is a bargain compared with the typical cost of a similar studio at market rate — an average of $1,491 a month, according to an analysis by Apartments.com this month.

In many ways, the arrangement between Wood and his friend is exactly what policymakers had in mind when crafting Seattle’s current backyard cottage regulations. For years, local lawmakers have touted accessory dwelling units — the technical term for self-contained apartments or houses that are built adjacent to the primary house on a given property, such as the studio Wood built in his backyard — as one way to mitigate the housing shortage.

“Seattle has a housing crisis, and we have a responsibility to grow the supply of housing options as quickly as possible,” said former Seattle Mayor Jenny Durkan in 2019 after signing municipal legislation that loosened restrictions on the development of accessory dwelling units. Before, there had been vocal opposition among some residents against these types of construction. The Queen Anne Community Council, for instance, had argued that such legislation would accelerate gentrification, undermine neighborhood stability and strain shared resources like parking.

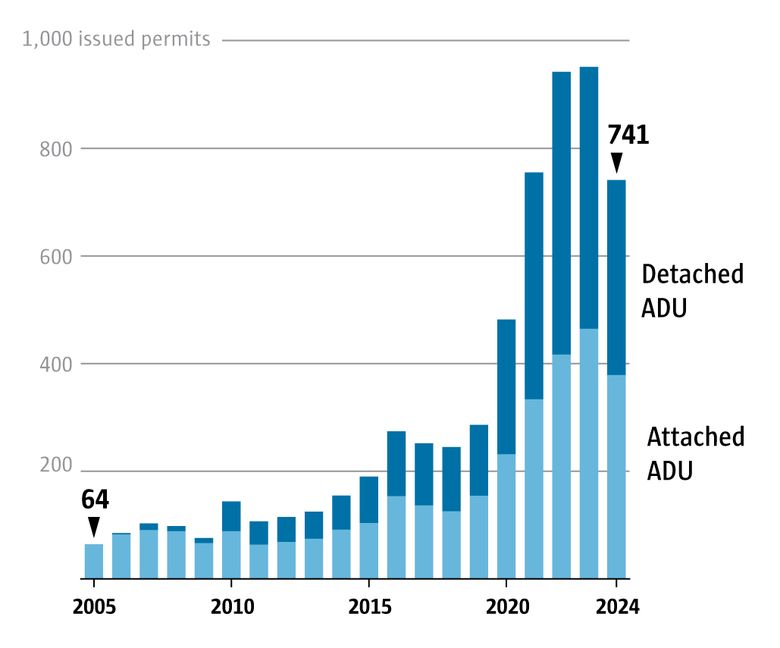

In the five years since, the city has seen a major uptick in interest. In 2020, the number of accessory dwelling units permitted jumped over 68% compared with the year before and continued to rise until peaking last year. In the past five years, close to 4,000 permits have been issued for accessory dwelling units, with over 2,000 for detached units and over 1,800 for attached ones. They comprise more than half of the permits issued for accessory dwelling units in Seattle under the current permitting system, according to data that dates back to 1994. (Not all projects that get permitted end up getting constructed.)

“That’s the promise of accessory dwelling units — that people will build housing for friends and family and rent below market,” said Bruce Parker, a designer who has worked in the sector since 2009 and witnessed its rapid growth.

In September, while introducing new proposals that would incentivize further construction, Seattle Mayor Bruce Harrell called them “an efficient, sustainable option to address the housing shortage.”

But this type of housing is far from addressing all of Seattle’s affordable housing needs. Recent estimates project that Seattle will need 112,000 new homes by 2044 to accommodate growth, with 44,000 for residents making less than 30% of the area median income.

For those building accessory dwelling units from the ground up, the process isn’t always rosy. Wood’s generous project made affordable housing possible for his friend. But it wasn’t exactly seamless for Wood himself.

Wood had originally estimated that the backyard cottage would cost around $200,000 to construct. In the end, the unit cost between $240,000 and $250,000 to construct due to unexpected costs, including high prices for lumber and concrete. They made up for the difference by dipping into savings.

Another unexpected cost came in the form of interest rates. When they first moved to Seattle in 2021, the interest on their mortgage was a low 3%. When they took out a home-equity loan to finance the accessory dwelling unit in early 2023, rates were as high as 9%, he said. “We had bad timing.”

The couple make a combined income of between $350,000 and $400,000 before taxes. Between their house and backyard unit, they now have two mortgage payments totaling close to $7,000 a month. They also make monthly student loan payments.

The rent Wood charges his friend covers utilities and a monthly King County sewage capacity charge on new wastewater infrastructure. But the rent is far below the monthly payment Wood pays on the unit, around $3,000 a month.

“Rental income is not what we’re getting out of it,” Wood said. “We charge a very low rent to try to help him out a little bit.”

Still, they have no regrets, and they are thrilled that the city’s accessory dwelling unit laws made theirs possible. If their friend ever moves out, the studio could be a home for family members. Their day-to-day life is better for having their friend so close, in a neighborhood they love. “We’ve got a little commune,” Wood said.

Multigenerational housing

For some families, accessory dwelling units make affordable housing possible by allowing members to collectively pool their resources and split costs.

In 2019, Patricia Blakely, 71, began contemplating her options for moving closer to her children. Blakely owned her home in Duvall, but her daughter wanted her nearby in Seattle. The idea was that in the present, Blakely could help take care of her grandchildren, and in the future, Blakely’s children could help take care of her.

The family conducted a compatibility trial run in 2020, with Blakely, her daughter and her son-in-law living together in a West Seattle rental house for a year. It worked out well enough that the family decided to commit to living together long-term, and they began looking for houses either with an accessory dwelling unit or the space to build one.

This arrangement suited Blakely financially, as well. In Seattle on her income — about $2,600 a month in Social Security — she wouldn’t be able to afford her own apartment, not to mention other costs.

“If I were renting, with the cost of the market in Seattle, my Social Security would barely cover rent,” said Blakely. “I would be tapping my savings all the time.”

In January 2020, Blakely’s daughter and son-in-law found a house within their budget in Shoreline with a large lot measuring 13,000 square feet. It also included a detached two-car garage, which they immediately began to convert into a detached accessory dwelling unit.

Construction began in mid-2021 and was completed over a year. In mid-July 2022, Blakely moved into her new home, a one-bedroom house that measures 700 square feet. It has a bathroom, living room, laundry room and “efficient” kitchen. The family also ensured that it was wheelchair accessible. “We built it specifically so that it would be good for me as I aged,” Blakely said.

The unit ended up costing around $200,000. To finance it, Blakely and her daughter agreed on a specific arrangement beforehand: Blakely would use the proceeds from selling her house in Duvall to pay for initial construction. In exchange for her investment and the value it added to the house, Blakely would then live there rent-free for as long as she liked.

Since moving in, Blakely’s cost of living has plummeted, given that she no longer pays for housing. Social Security more than covers her other expenses — essentials like car costs and Hulu, she joked — and she typically has some money left over to add to her savings each month.

“It’s better than I could have hoped for,” she said, reflecting on the financial arrangement.

Room for growth

Some Seattleites see in the burgeoning backyard cottage industry an opportunity for work and income.

Cory Tobin, 35, used to work converting Sprinter vans into campers. In 2020, he and his wife bought their first house in Ballard. Looking out at his backyard one day, he was struck by the idea that it was big enough to fit another house. Having worked as a contractor in the home renovation field, he wondered if he might be able to build it himself.

Despite a steep learning curve, he completed building the detached accessory dwelling unit in October 2021 — a 1,000-square-foot, two-bedroom, three-bathroom stand-alone house on the alley side of his property. It had a kitchen, living room, office space and even a fireplace. He then created a homeowner’s association between his own house and the detached accessory dwelling unit, split the latter off as its own condo and sold it. (Tobin declined to share how much he made off the renovation and sale.)

Using the proceeds, he bought another house in Green Lake and repeated the process. In the backyard, he built a stand-alone house. Meanwhile, he split the main house into two apartments, by renovating the basement into a self-contained unit. He rents out both and sold the backyard cottage as a separate condo.

He repeated the process a third time with another house in Green Lake, completing construction of the detached accessory dwelling unit in March. Turning single-family houses into multifamily condos, enabled by Seattle’s accessory dwelling unit laws, has become his full-time line of work.

“Relaxing the (detached accessory dwelling unit) regulations in order to create more housing in Seattle is working,” he said. “My most recent property in Green Lake had just one person living in it before I purchased it. Now there are six people.”

Affordable housing solution?

While accessory dwelling units have put affordable housing within reach for some, their impact on a larger scale has been less evident.

“Every unit that is providing housing for someone who isn’t living somewhere else is increasing the regional housing supply,” said Emily Hamilton, senior research fellow and director of the Urbanity Project at the Mercatus Center at George Mason University.

Hamilton has written extensively about ADU legislation. “And there’s a lot of research showing that increased housing supply improves affordability for people up and down the income spectrum.”

Backyard cottage construction might ramp up in the coming years thanks to changing legislation. In 2023, the state Legislature passed House Bill 1337, one of the strongest laws in the country in terms of enabling homeowners to build accessory dwelling units. The law would allow for more and larger accessory dwelling units across the state while doing away with restrictions like owner-occupancy requirements and certain parking mandates.

Critically, it’ll allow the construction of up to two detached accessory dwelling units per lot. In September, Seattle Mayor Harrell also announced a forthcoming municipal proposal to allow units measuring up to 1,500 square feet each. In general, Seattle code — which must be updated to adhere to state law by June 2025 — currently limits construction to one detached unit and one attached unit, each measuring 1,000 square feet or less. (Alternatively, construction of two attached units is also allowed.)

But even with strong laws, plenty of obstacles remain in the way of more widespread construction. For existing homeowners, it can be costly to take out a second mortgage to fund additional housing. Today, that can be exacerbated further by persistently high mortgage rates.

To alleviate these pressures, some banks are adapting to the proliferation of accessory dwelling units by creating dedicated financing for them. In October 2023, the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development announced a policy that allows lenders to count income from backyard cottages when underwriting mortgages — a move that agency executives claimed would help homeowners build wealth and communities create affordable housing.

At the end of the day, the impact of policies encouraging the construction of backyard cottages will depend largely on the scale at which they’re built. And in Seattle, that scale remains relatively small.

As Hamilton pointed out, construction of accessory dwelling units comprises a fragment of total homebuilding compared with that of multifamily units. So far this year, 741 ADUs have been permitted. By contrast, 4,569 units in multifamily buildings were permitted between January and October this year, according to preliminary data from the Census Bureau’s building permits survey.

Each individual accessory dwelling unit could make a world of difference for the person moving in — be that a best friend, family member or homeowner creating an income stream. But the broader ramifications so far appear to be more muted in Seattle, Hamilton said.

“If we were to look at a chart of total housing supply, ADUs aren’t making a huge difference in that.”