The Seattle Times Editorial Board invited representatives from the opposing sides of Initiative 2117 to debate the complexities of the state’s landmark climate law — and what happens if it is repealed. Brian Heywood, founder of the organization that funded a raft of fall initiatives, joined Washington Policy Center Vice President of Research Todd Myers in arguing for the Climate Commitment Act’s repeal. Rep. Joe Fitzgibbon, D-West Seattle, one of the architects of the act, defended it, alongside Seattle Metropolitan Chamber President Rachel Smith.

Thanks to TVW, you can watch the debate at st.news/2117.

Here are some claims made during the Aug. 15 debate, and the editorial board’s analysis to separate the fact from fiction.

“It’s gonna cost you, maybe a couple thousand bucks extra a year.”

CLAIM: Heywood argued that the average Washingtonian is on the hook for $300-$500 a year in gas, $500 for home energy costs and $200-$500 for groceries due to the Climate Commitment Act’s auctions on the state’s largest polluters.

REALITY: There is a lot to unpack here. Buckle up.

The state’s 100 or so biggest greenhouse gas emitters participate in quarterly auctions where they purchase allowances for each metric ton of carbon pollution they produce. This impacts their bottom line, and those costs are passed along, including at the gas pump. Critics of the auctions argued the price per ton was too high in Washington’s market — at times around $60 when it should have been lower, say, closer to $25. Proponents and foes alike acknowledge that drove up the cost of gas in the state.

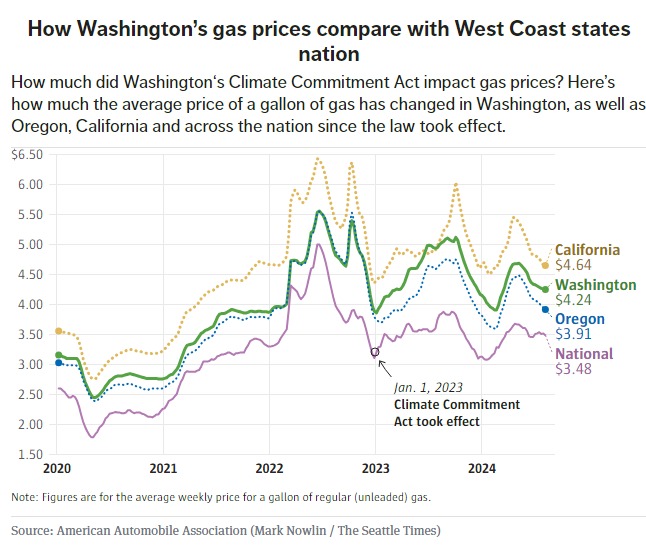

But by how much? The best metric might be the price difference between gas prices in Washington and Oregon, which have been historically similar. But Washington’s prices have edged up since the act took effect (see chart).

Myers’ own analysis found 2023 gas costs — both for motor vehicles and home energy — increased for an average Washington family with two cars by between $450 and $630 per year. He and Heywood’s numbers may be close but it’s impossible to know for sure, given the complexities of fuel prices.

The cost of gas has also fallen this year in Washington. Heywood argues that market participants have backed off this year — thinking voters may kill off the market in November. Thus, auction demand and cost of allowances are lower, which in turn decreases the price at the pump. Fitzgibbon argued that the Legislature’s decision to “link” Washington’s market this year with the carbon markets in Quebec and California — is what is leading to a price decrease and overall stability.

So, it’s speculative to assert exactly how much prices have gone up — and it would require guesswork to predict how much they’d go down if 2117 passes. The “no” campaign argued that, with all that goes into a gas price, there is no guarantee they’ll fall. Myers said he was certain they would.

“(If the act is repealed) we’re going to have to take that money out of highway projects.”

CLAIM: Smith and Fitzgibbon insisted that a repeal of the act would have dramatic ramifications for the state’s transportation budget. However, the Legislature prevented money raised in the act’s auctions from funding highway and vehicle travel infrastructure projects. The yes campaign criticized the tactic of suggesting those projects would be on the chopping block if I-2117 passes.

REALITY: For clarity, it helps to go back to 2022, when the Legislature passed the $17 billion Move Ahead Washington transportation package. Lawmakers tied $5.4 billion of Climate Commitment Act auction dollars to that package.

Fitzgibbon noted that the act’s funding includes construction for a new fleet of hybrid-electric vessels for the Washington State Ferries. “If we lose the revenue stream … we’re not just going to stop building ferries … we’re going to have to take that money out of highway projects.” Thus losing the act’s funding won’t directly affect road and bridge projects, but will impact them by shrinking the entirety of the transportation budget. In other words, if the initiative passes, lawmakers will have to decide what stays in the overall existing budget, and what is cut.

“We don’t have data on CO2 emissions since 2019.”

CLAIM: Myers put it plainly: If the Climate Commitment Act’s mission is to reduce carbon emissions in the state, why hasn’t it done so yet?

Heywood made unsubstantiated claims that BP, which operates Washington’s largest oil refinery, has supported the Climate Commitment Act because of either A) a “deal” or B) a “threat” from Gov. Jay Inslee.

Not true, Cesar Rodriguez, a company spokesman, told the board.

Tom Wolf, BP’s senior government affairs manager for the West Coast, previously told the board that BP “has consistently said it supports an economy-wide, market-based price on carbon.”

That support is even listed on the company’s web site under its sustainability goals.