Agreed.

https://www.seattletimes.com/opinion/editorials/dismal-student-scores-make-clear-normal-doesnt-cut-it/

By

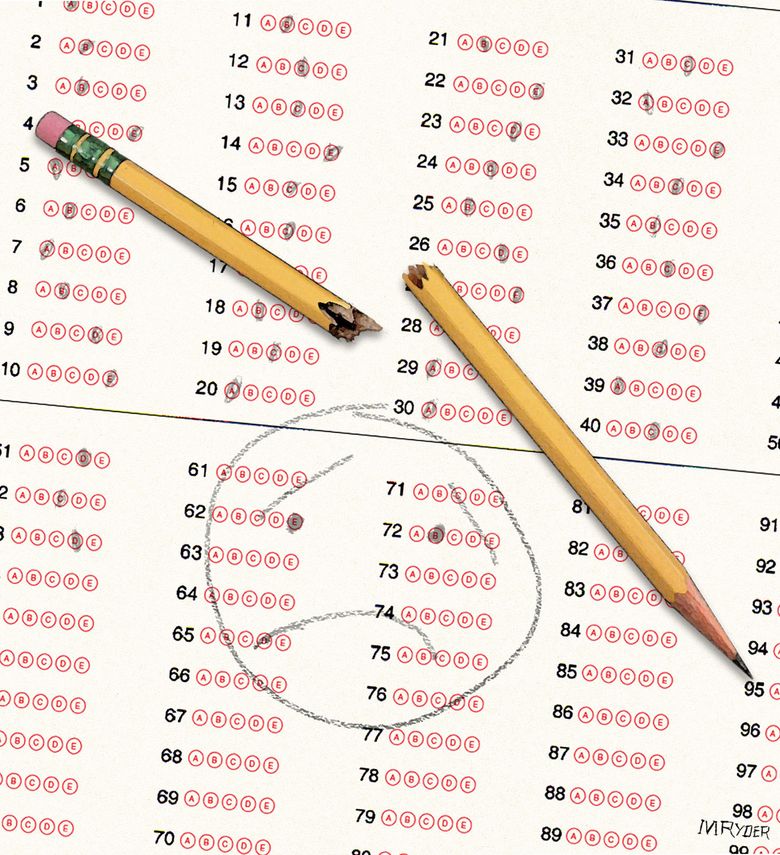

Grim as they were, the recent release of student assessments known as “the nation’s report card” should have surprised no one. Education researchers say the effects of learning disruption during the pandemic are worse than what kids in New Orleans faced after Hurricane Katrina.Yet, 92% of parents believe their children are working at or above grade level, according to the Learning Heroes national survey of parents, teachers and principals.

The truth is, only 28% of Washington eighth graders are currently proficient in math, a drop of 13 points since 2017. Overall, the pandemic wiped out decades of slow academic improvement, pushing us back to where we were in the 1990s.

Some will note that Washington students are still doing better, on average, than kids in 21 other states, according to the National Assessment of Educational Progress. But averages blur glaring — and important — extremes. Consider the ocean of difference in math scores between low-income eighth-graders and middle-class kids: a 31-point gap that is among the widest in the nation.

If ever there was a moment to do something different, surely this is it. Yet the prevailing attitude in most school district headquarters might best be described as a desperate effort to get back to normal. Understandable. But when “normal” in math achievement means a gulf between Black and white students on par, or worse, than that in Mississippi, it’s time for new answers.

State Sen. Brad Hawkins, R-East Wenatchee, floated legislation aimed at this problem during the pandemic. It didn’t pass, but the central concept — modifying the traditional school calendar — is gaining traction with some school districts anyway.

Sometimes referred to as “year-round learning,” the modified calendar takes our state’s standard 180 days of school and, instead of cramming them into nine months, spreads the time more evenly throughout the year. Yes, that means shortening summer break. It also means students don’t spend their first month of school reviewing what they were taught 11 or 12 weeks earlier. If students are going to catch up, they can’t afford to waste that time.

Educators in 43 state school districts appear to agree. They are either studying or implementing modified calendars. In tiny Winlock, south of Olympia, that means extending the school year by three weeks — with vacation days added to October and February instead. In Toppenish, the modified schedule shows up as longer school hours Monday-Thursday, with Friday afternoons reserved for tutoring. The guiding concept is responsiveness to student needs, rather than fidelity to a calendar designed when the U.S. was an agrarian society.

It’s early still. But teachers in Winlock are already reporting better behavior among their students — only 19% of whom were at grade level in math last spring.

A more targeted response, high-dosage tutoring, also has shown results. It’s expensive, requiring one-on-one sessions between teachers and students at least three times a week. But Washington received $1.6 billion in federal aid to cover exactly this sort of intervention. To date, a perplexing 68% of that money remains unclaimed, according to the state Superintendent of Public Instruction.

It’s puzzling to examine school district spending choices so far. Though they have until September 2024 to use the funds, only 9% of the learning recovery dollars have gone toward intensive tutoring and social-emotional support for kids. Just 3% has been spent on helping disadvantaged students. The bulk has instead funded sanitation and bookkeeping costs collected under the label “Other.”

As Sen. Hawkins points out, Washington has made enormous investments in education during the past 10 years, responding to the McCleary ruling. Yet the school system itself seems the same as it ever was.