Just over 50 years ago, Washington voters approved Initiative 276, which demonstrated the citizenry’s righteous desire to keep tabs on their elected officials. With that vote, the state Public Records Act established the right of the public to have access to the machinations of government. It also created laws to require robust disclosure of who is funding campaigns and possibly influencing elected officials.

In statute, the people placed these desires for the elected officials:

“The people of this state do not yield their sovereignty to the agencies that serve them. The people, in delegating authority, do not give their public servants the right to decide what is good for the people to know and what is not good for them to know.”

RELATED

Sunshine Week: Learn more about your right to know

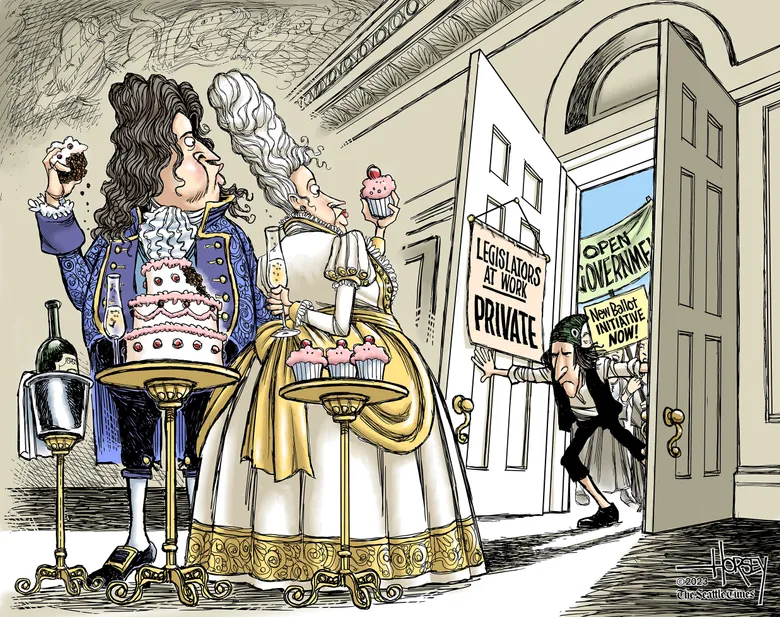

Pretty clear. Sadly, however, many lawmakers have lost their way, even doubling down on self-dealing moves to keep secrets from their constituents. Whether they lose in court or are inundated by constituents calls when their shenanigans are revealed, as happened in 2018, they just haven’t learned their lesson.

Recently, during a dramatic meeting of the Sunshine Committee when a member resigned over lawmakers’ yearslong indolence on acting on its recommendations, another member, David Zeeck, shared the frustration. Maybe, the former publisher of the (Tacoma) News Tribune suggested, advocates should go over the heads of lawmakers once again.

“Maybe that’s what’s going to be required to correct this. Let somebody besides the Legislature — the people of Washington state, perhaps — codify how we deal with exemptions,” Zeeck said.

He’s right. Time to ask the people to affirm their intention to control their government, not the other way around.

In full disclosure, I am a board member for the Washington Coalition for Open Government. WashCOG is a nonprofit dedicated to keeping the sunshine on government at all levels — from state agencies to the Legislature to city councils, and hospital and school boards.

The WashCOG board has not reached any conclusions, but members are discussing the option of a citizens initiative as a last resort.

So, let’s make the case for a ballot measure, using lawmakers’ past actions to do it.

Exhibit A: Lawmakers balloon records exemptions

When voters approved I-276 in 1972, the Public Records Act had only 10 exemptions, including having to do with personnel issues and real estate transactions for fair reasons.

By 2007, legislative mischief makers had codified hundreds more exemptions for a total of about 300. So concerned about the number, then-Attorney General Rob McKenna requested a bill to create the so-called Sunshine Committee, comprising media members, advocates, other members of the public and four lawmakers to review exemptions and make recommendations about whether they should stand.

Did lawmakers slow down in their efforts to keep their secrets? In a word, no.

Exhibit B: Legislature squanders Sunshine Committee opportunity, ignores recommendations

In the time since, the Legislature at least doubled the number to more than 600 exemptions. In 15 years, lawmakers have enacted few of the Sunshine Committee recommendations. This year, not one of the committee’s lawmakers — Sens. Sam Hunt, D, and Jeff Wilson, R, and Reps. Larry Springer, D, and Jenny Graham, R — lifted a finger to introduce the committee’s recommendations as legislation.

Sen. Hunt, himself, emailed a constituent questioning that fact. “I question whether or not the Sunshine Committee should continue to exist,” concluded the powerful chair of the Senate State Government, Tribal Relations and Elections Committee.

Definitely not the words of an open-government champion.

At the Feb. 28 meeting, public records lawyer Kathy George, an eight-year committee member, resigned in frustration.

“We can’t get a bill passed. We couldn’t even get a bill introduced,” she told a Times reporter. “And it just doesn’t seem like the Legislature is likely to remove the exemptions.”

Exhibit C: The Legislature tried to exempt itself from the PRA and the constituents revolted

In 2018, the people gave the Legislature a swift course correction when it tried to pull a fast one by exempting itself from the Public Records Act.

A group of news organizations, including The Seattle Times, had sued the Legislature to gain access to some legislative records, including emails. The state Supreme Court ruled that, indeed, the Legislature was subject to the PRA. Within weeks, House and Senate leaders on both sides of the aisle schemed to flout the ruling. Both houses, on the same day, passed a law that would exempt the Legislature from the Public Records Act. With a veto-proof majority, no less.

Instigated by The Times editorial page, a dozen Washington newspapers ran front-page editorials just as the governor returned from an East Coast trip. They urged readers to: Contact the governor and urge him to veto the bill; and contact their lawmakers to urge them to stand down and not override the veto. The governor’s office reported it received such advice from about 20,000 citizens and many lawmakers reported contacts numbering in the hundreds.

Two days later, Gov. Jay Inslee vetoed the bill and three of four legislative caucuses announced they would not override.

The people prevailed. Or so we thought.

Exhibit D: Legislative lawyers create a dubious “legislative privilege“

Emanating mostly out of the House Democratic caucus, lawmakers have started to invoke something called “legislative privilege.” I hope the lawyers who came up with this concept of legislative privilege have enough ice to soothe their pulled muscles. Their guidance to lawmakers is that they can just say no to records requests. And if the document in question is an email with others on the thread, those lawmakers must actively opt out of the privilege; not opt in.

The legal argument is based on an unrelated constitutional provision, that merely says lawmakers cannot be sued or criminally charged with anything hey say in debate. It says nothing about the documents they create.

Exhibit E: Redistricting Commission flouted the state Open Meetings Act with partisan legislative leaders

Washington state’s Redistricting Commission is activated every 10 years to adjust electoral districts to reflect changes the U.S. Census reveals. Ostensibly, it is designed to be an independent body comprising one appointee each from the four partisan legislative caucuses. They then agree on a nonvoting, nonpartisan chair.

Rather than serve communities with public meetings, the 2021 process devolved into backroom dealing, meetings and decision-making out of the public view. In an Open Meetings Act lawsuit, depositions revealed legislative leaders were pulling strings behind the scenes, attorney Joan Mell said. The commission paid $135,000 to settle lawsuits brought by WashCOG and an individual. Additionally, each of the five commissioners had to pay a $500 fine.

These are just five examples of the Legislature’s egregious abuses of the public’s right to know.

I should say here, not all lawmakers are in cahoots with this trend, bless them. But, taken together, these are actions of a state Legislature, over years, whose ethos has evolved into one in which members think they know best. Legislative leaders have become emboldened by decreasing scrutiny of independent media organizations on the decline. And they have become more beholden to special interest groups that have become more powerful in the vacuum created.

When traditional journalism organizations, whether print or broadcast, have fewer resources, that is the time when open government laws are the most important. Individuals, organizations and businesses should have the right to access what lawmakers have been seeking to hide.

Collectively, the Legislature isn’t suddenly going to change its power-preserving proclivities.

The people will need to. Time to consider another voter-enacted open government law.

What that looks like is up for debate. Stay tuned.

Kate Riley on Twitter: @k8riley. is the editorial page editor at The Seattle Times: kriley@seattletimes.com; on Twitter: @k8riley.