Article Summary:

Outside experts warn that Sound Transit light-rail extensions, already years late, will careen into endless delays unless the board and executives adopt a big-time mindset to match the 116-mile network they promised the voters.

That means a harder line dealing with 53 local governments, which sometimes view transit projects as a piggy bank for local streetscape improvements. It means treating contractors better, so they’ll bid for future work.

And the transit board must rebuild trust between elected officials who excessively seek more studies and the professional transit staff who’ve been too shy about exposing problems.

These themes appear in a report issued Thursday by an eight-person technical advisory group formed in mid-2022, in hopes of reducing delays to the nation’s most ambitious transit-expansion plan. Transit board members Claudia Balducci of Bellevue and former Chair Kent Keel of University Place asked for the panel after a $6.5 billion shortfall was revealed two years ago.

Every month, the price to build a 12-mile Ballard-to-West Seattle train corridor rises $50 million, said co-author Grace Crunican, former head of Bay Area Rapid Transit and the Seattle Department of Transportation. Current estimates are near $15 billion, and likely to rise, compared with $9 billion projected in 2016. Not just transit staff but the board, local communities, federal overseers and contractors need a new perspective, she said in an interview.

“They need to get to a culture of, ‘Do the job and get it out the door,’ and keep in mind every minute, that time is money,” she said.

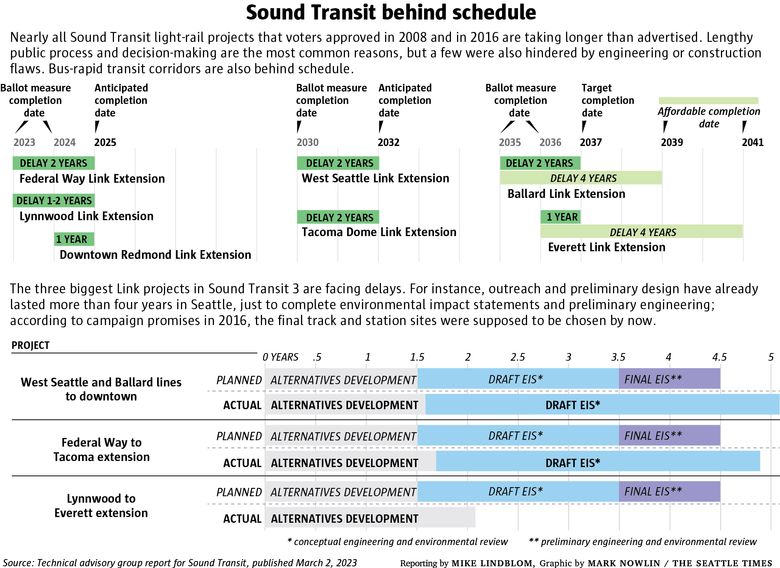

Most lines in the winning Sound Transit 2 ballot measure of 2008, and Sound Transit 3 lines voters approved in 2016 through property, car-tab and sales tax hikes, are behind schedule. The ST3 campaign maps displayed a dozen megaprojects: faster freeway buses, longer Tacoma streetcar tracks, Sounder commuter-train improvements and light rail reaching Everett, Issaquah, Redmond, Tacoma, West Seattle and Ballard.

One common denominator is the sluggish pace of decision-making, the report emphasizes. A few lost additional time to construction or engineering problems, an angle not plumbed by the 42-page document.

Light rail to Ballard is projected in 2039, and Everett service by 2041, each four years later than advertised. But a pair of Redmond stations will arrive only a year late in 2025, as did the Northgate extension in 2021.

Just this week, Sound Transit acknowledged its line from Federal Way to Tacoma won’t open until 2035, five years late. New station sites are being explored to avoid floodplains and Indigenous cultural resources.

Sound Transit 2 and 3 together could extend today’s 24-mile light-rail network, which carries 80,000 daily riders, to 116 miles in three counties (similar length to the Washington, D.C., subway). The finance plan estimates total capital, finance and operating costs for all services at $149 billion from 2017 to 2045.

“[Sound Transit’s] work to date benefits thousands of riders every day,” the report concludes. “Without significant investments in change, the sheer volume of work associated with ST3 will overwhelm the agency as it is currently structured and functioning.”

Sound Transit board Chair Dow Constantine said he wants to continue hearing from the advisory panel. CEO Julie Timm will formally respond in April.

“Sound Transit has a lot going for it, but it is entering uncharted territory now, with a fivefold increase in work and a sixfold increase in capital spend. And it needs to become a bigger and different agency in order to successfully execute,” said Constantine, who is King County executive.

Crunican emphasized Thursday while briefing board members that Sound Transit faced many difficulties in the past few years.

“I want to put in a word for the existing staff,” Crunican said. “You didn’t get here because you have a bad staff. You got here because you have a lot on you, and probably in 2016 didn’t plan for the work that had to be done.”

Taming the process

For the Seattle route, environmental studies and final decisions on station sites were to be completed by now. After five years of planning, the board has made progress by narrowing the station options in difficult spots like the Chinatown International District. But they’re far from done.

Sound Transit’s slow pace has been called out before, not only in local news media coverage but also in national studies from the nonpartisan Eno Center for Transportation and New York University’s Transit Costs Project.

EnoTrans focused on “overcustomization” by Sound Transit to slake community demands and the average five-year planning phase. NYU remarked that Seattle-area voters approved ST3 projects “based on 1-2% design, which one former official described as ‘a drawing on a napkin’.” Consequently, politicians on the Sound Transit board interfere more than New York leaders during project design, NYU said.

Thursday’s report suggests giving managers power to ignore unworkable concepts. “Studying improbable alternatives suggested by the board, the public or others during the planning and design phase wastes time and distracts the project team from its goal of advancing progress,” it says, without naming specific examples.

One such infeasible option was to build the future South King County train-maintenance base atop the defunct Midway Landfill, along the corridor from Angle Lake to Federal Way and Tacoma, panel member Eric Goldwyn, an NYU researcher, said Thursday morning. The studies found it would require a thick concrete layer and add more than $1 billion; Sound Transit ultimately chose a South Federal Way site instead.

To add clout and experience, Sound Transit should hire a capital projects director, a deputy to oversee ST2 routes (projects as Bellevue and Lynnwood), and one for ST3, the report said. The agency should recruit worldwide for executives who’ve led multiple projects simultaneously, and their pay will likely exceed the $375,000 CEO salary, Crunican said.

“Betterments”

The panel called for a clear policy to avoid add-ons by local cities, such as road widenings. As a hypothetical, Crunican said Sound Transit would finance 10-foot-wide sidewalks at stations, but to have 12 feet, a city must contribute.a more profound question regarding Ballard, where Sound Transit proposed a stop at 14th Avenue Northwest, but Seattle prefers 15th Avenue Northwest, which is closer to the retail district and apartments. Crunican said she’d consider that a “betterment” in which the city should chip in the $200 million difference. (A newly charted version, involving street right of way, would trim the increase to $70 million.)

Projects are complicated by cities that can withhold permits and seek betterments as leverage, when the agency closes a street or builds a station, the report says.

The experts encouraged Sound Transit to consider wielding its power as an “essential public facility” in state law, rarely used, to preempt local jurisdictions.

Sound Transit invoked that doctrine in 2002 to override the Tukwila City Council, which wanted a costlier route serving Southcenter mall and threatened to withhold permits. Instead, the agency with federal consent picked a more direct, cheaper path along freeways toward Tukwila International Boulevard and the SeaTac/Airport Station.

Seattle Mayor Bruce Harrell aired some hesitation Thursday morning about cracking down on “betterments,” noting Seattle is far bigger than neighboring cities with intense competition for downtown space.

New York is considering a 30-day time limit for utilities to review transit-related relocations, while Toronto’s agency takes over permitting within 50 feet of its trackway and Italy holds rapid meetings where each government sends one person to hash out development questions, the report said.

Contracting crisis

Construction firms internally price an extra 15% into their Sound Transit bids, to offset hassles and delayed payment, a plight shared with Boston and New York, said Goldwyn. Along the Federal Way extension, an average 260 days elapse between “change orders” and when builders get paid for extra or different work, because of friction within the agency, Crunican explained. On-site engineers need approval from higher-ups for decisions over $50,000, compared with $5 million for private firms, the report says.

“Two reputable firms who worked on ST2 projects indicated to the [panel] they will stop bidding on future ST projects,” says the report.

The experts hoped new capital executives can raise Sound Transit to an “owner of choice,” like the smooth relations between contractors and the Washington State Department of Transportation.

Crunican led Seattle DOT under Mayor Greg Nickels in the 2000s, when the city fixed potholes, launched its first modern streetcar and passed a levy for work like seismic strengthening and a new Mercer Street. Nickels and SDOT drew public ire in a December 2008 snowstorm when roadway ice lingered for days, because of SDOT’s now-abandoned policy to not use salt. Other panelists familiar to Seattleites are Ken Johnsen, a construction executive at Climate Pledge Arena, and Greg Johnson, administrator for a proposed Interstate 5 bridge replacement between Washington and Oregon.

Balducci, also a Metropolitan King County Council member from Bellevue, said she would do everything possible to move projects faster. She recalled the 2016 campaign, when voters were baffled at grand opening dates like 2035. Then during the pandemic, inflation and concrete drivers’ strike, the board reluctantly pushed back ST3 timelines a couple of years. “We choose the ‘delay’ lever every time,” she lamented.

Despite many critiques, the report says it’s still possible to scale back delays so trains arrive closer to when voters were promised.