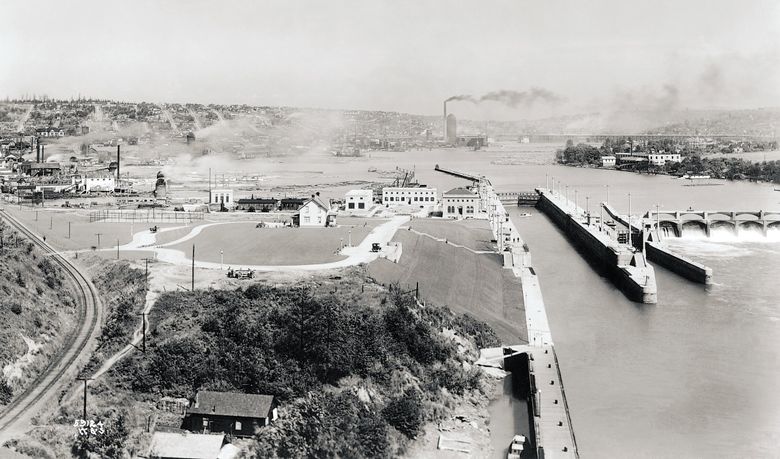

THREE YEARS AGO, a Washington state senator from Ferndale introduced a bill to study the costs and benefits of breaching the Ballard Locks.

Republican Doug Ericksen, who died in 2021, didn’t really expect it to happen. His legislation was a jab at Seattle liberals calling for removal of dams on the lower Snake River to benefit salmon and orcas.

Taking out the Locks would “tear out the heart” of the city, one witness testified at the only hearing before the measure failed. By connecting Puget Sound to lakes Washington and Union more than a century ago, the officially named Hiram M. Chittenden Locks and Lake Washington Ship Canal transformed Seattle’s landscape, economy and society so profoundly, it’s hard to imagine rolling it all back.

“I’m not against removing dams,” says David Chapman, project engineer for the facility, which is operated by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. “But this is a dam you can’t undo.”

One hundred and six years after they formally opened in 1917, the Ballard Locks are the nation’s busiest, passing up to 50,000 vessels each year. As Lake Washington’s only outlet, the Locks and spillway maintain the near-constant water levels required for the Interstate 90 and Highway 520 floating bridges. If the Locks were removed — or knocked out by an earthquake — the lake would equalize with Puget Sound, dropping up to 20 feet and leaving thousands of docks, moorings — and some of the country’s costliest waterfront mansions — high and dry.

The combination of freshwater moorage and ocean access provided by the Locks is a big reason a $670 million commercial fishing industry calls Seattle home. A 2017 study found the Locks support maritime businesses that employ 3,000 people and generate more than $1.2 billion in annual sales.

Even local tribes, whose historic fishing grounds were devastated by the project’s radical replumbing of watersheds that nurtured their ancestors for millennia, aren’t pushing to have the concrete barriers yanked.

“The only way to really fix it is to take them completely out, and that’s not going to happen,” says Rob Purser, fisheries director for the Suquamish Tribe. Instead, the tribes’ goal is to reduce the toll on salmon as much as possible.

But despite the Locks’ pivotal place in the state’s biggest city and economy, funding to keep the aged facility functional and improve fish passage has been very hard to come by — until recently.

FOR DECADES, the Ballard Locks got short shrift from the Corps of Engineers based on a funding formula that favors tonnage transported, not vessel traffic. With recreational boats accounting for more than 75% of its users and a fishing fleet that unloads most of its catch in Alaska, Seattle’s Locks were low on the priority list.

“It seems like they were only able to get funds to fix things once they were red-tagged,” says Jason Mulvihill-Kuntz, of the Lake Washington/Cedar/Sammamish Salmon Recovery Council. “I give them a lot of credit for making the thing work with duct tape and baling wire.”

As the facility approached its centennial, so much machinery was failing — including an emergency closure crane from the 1920s — that inspectors downgraded its safety rating from 4 to 2 on a scale of 5, meaning urgent attention was needed. Business and community leaders mobilized, commissioning the 2017 economic impact study that identified up to $60 million in needed repairs. Conservation groups and Washington’s Congressional delegation joined tug operators and shipyards in lobbying for more money — and it paid off.

Over the past six years, the Corps has spent or committed more than $65 million to upgrade or replace antiquated equipment, with some of the money coming from the 2021 Bipartisan Infrastructure Bill. Another $40 million in improvements is queued up over the next two decades.

“This is one of the most exciting times to be at the Locks since it was originally built,” says Chapman. “If you walk around and point to almost anything, we’ve either done a project on it, or we’re scheduling a project on it.”

One of the biggest jobs, the $18 million replacement of the center gates in the largest of the two locks, is scheduled to start this month. Weighing nearly half a million pounds each, the hollow-chambered structures are nearly impossible to repair and already have lasted longer than anyone expected, says Chapman.

“Infrastructure like the Locks generally has a 50-year design lifetime, and here we are more than 100 years in, and just getting this work done.”

ON A SUNNY DAY in August, the Locks are thronged with people. Some crowd into the fish ladder viewing area to watch a surprisingly robust run of chinook salmon fighting their way upstream. Others gawk as a 120-foot motor yacht with a matching SUV on its deck glides out of the large lock. A gaggle of grade-school boys pushes bikes across a walkway to the opposite bank.

With more than 2 million visitors a year, the Locks and their grounds — including a botanical garden and museum — are one of Seattle’s top attractions.

But the public rarely sees the inner workings, Chapman says, descending a circular staircase with a brass railing to subterranean chambers below the administration building. The first floor down is occupied by the original pump motors and electrical panel — state of the art in 1917, now preserved for their historic value. The current electrical system, which dates from the 1970s, isn’t much better, Chapman says, opening a cabinet to reveal a tangle of wires patched with tape.

“This is such a mess,” he says, but a major upgrade is coming.

On the lowest level, five stories down — dark and musty — Chapman points out new pumps used to dewater the Locks for annual maintenance. They were replaced in 2017, after one of the original cast iron pipes burst.

Chapman ducks into a cramped tunnel where rusted and jury-rigged cable trays carry utility lines under the Locks. Water drips from the ceiling. “This is such a corrosive environment,” he says. “We’ve got about 55 feet of water over us here.”

Back aboveground, Chapman pops a hatch by the small lock, revealing a grimy chamber that houses the machinery to open and close the gates and valves. Gears the size of a truck tire have to be greased several times a week. Modern controls will soon take their place, Chapman says, with a trace of regret.

“I kind of hate to see them go,” he says. “There’s something almost romantic about these old mechanical things.”

But the goal is to make the Locks more dependable, with fewer breakdowns and unplanned closures. Recent upgrades also helped boost their safety rating to 3, or moderate.

The biggest risk to the Locks is a powerful earthquake that damages the structure and prevents the gates from closing, says Richard Smith, dam safety manager for the Corps’ Seattle District. In a worst-case scenario, Lake Washington could drop 20 feet in four days. To prevent that, a new crane was installed at the large lock to deploy massive steel bulkheads and stop the outpouring of water.

(Even if the lake dropped several feet, the bridges could remain usable — though at much reduced speeds — if crews were able to respond quickly and tighten cables that secure the pontoons, according to the Washington State Department of Transportation.)

WHILE IT’S GREAT to see the Locks getting structural and mechanical overhauls, tribes and fish advocates would like to see more urgency around salmon survival.

“The Locks and Ship Canal are a huge bottleneck,” says Mulvihill-Kuntz. “Every fish in this watershed has to go through that facility twice: as a juvenile going to the ocean and as a returning adult.” Funneling the fish into a narrow corridor also leaves them vulnerable to predators such as seals and sea lions.

One of the recent upgrades that benefitted salmon as well as lock operations was the $13 million replacement of the garage-door-size valves that empty and fill the large lock chamber. Called Stoney gates for the Irish engineer who invented them in the 1800s, they originally were used in the Panama Canal.

In Seattle, it’s been clear since the mid-1990s that the valves, which were corroded and stuck on high speed, were sucking outbound smolts into culverts encrusted with barnacles. “It was essentially like a cheese grater,” says Mulvihill-Kuntz. “It would just shred them.” Annual barnacle scraping helps but doesn’t eliminate the problem.

The new valves, with adjustable flows, should be less dangerous to smolts, but it’s frustrating it took until 2021 to address a threat identified more than a quarter of a century ago, says Mike Mahovlich, assistant director for harvest management at the Muckleshoot Tribe.

On his priority list are several upgrades he hopes will get future funding, including modernization of the 1970s-era fish ladder. The structure has no way to exclude voracious pinnipeds, which sometimes park inside the ladder to feast on returning salmon.

A worsening problem is dangerously warm water and low oxygen levels in the Ship Canal. Temperatures in the shallow stretch between the Locks and Lake Washington sometimes exceed 70 degrees, which can be lethal to salmon. More than half of adult sockeye that made it through the fish ladder in recent years died before spawning, due to a suspected combination of heat stress and infection, says Mahovlich. High temperatures also seem particularly hard on Chinook.

Possible solutions, which include pumping deep, cold lake water into the Ship Canal, will be very costly. In the meantime, the Muckleshoot Tribe has been capturing adult sockeye at the fish ladder and rushing them by boat to a hatchery on the Cedar River.

Wild Chinook in the watershed remain threatened with extinction, but this year’s big run — which included hatchery fish — is heartening, Mahovlich says.

“There is hope that if we keep working at it and fixing these problems, we can have sustainable fish in this watershed.”

THAT THE LOCKS function as smoothly as they do is a testament to generations of workers who have tended the facility. Today’s staff numbers 64, including full-time gardeners who keep the grounds groomed and lush. Rangers lead guided tours and answer the “Where’s the bathroom?” question dozens of times a day. Biologists monitor fish and water quality.

The maintenance team keeps the geriatric machinery working — most of the time. Replacement parts for such old, specialized equipment can be hard to find, says maintenance chief Jeff Stander. Something’s always breaking, and workers sometimes have to fabricate components from bulk steel.

The biggest crew is the men and women who work the locks, guiding boats, shouting directions, handling lines and staffing the control tower. Anything that can happen will, says Mike Hand, a 14-year veteran with the enviable title of lock master.

He’s seen boats sink in the locks, and a tug underestimate its beam and get stuck. People fall overboard. Couples scream at each other. A pair of kayakers once was swept over the spillway — and survived. When a tug pushing a gravel barge lost throttle control, the Locks crew had to scramble to prevent lines from breaking and keep the heavy load from smashing the gate. “They slowed it just enough that it only made a small dent,” Hand says.

The Locks were constructed in part to spur an industrial boom, and for several decades, mills, shipyards and maritime operations proliferated on Lake Union. But a hoped-for Navy base went to Bremerton, and by the 1960s, pleasure boats outstripped commercial. Lakefront industries have been increasingly squeezed out by condos, yacht brokers, restaurants and parks.

On a Thursday afternoon in late summer, the ratio of commercial to recreational boats at the large lock is 1:9. The single working vessel is a fishing tender on its way back from Alaska.

Jason Bergerson, who has worked at the Locks for 13 years, is in the tower. Most pleasure boaters are nervous making the transit, he explains, so he projects a calm, radio announcer voice over the loudspeaker.

“Bigger vessels first,” he tells the waiting boats. “If it’s bigger than you, let it through.”

A small sailboat races ahead of the pack, and Bergerson sighs.

“This guy has an inflated view of his vessel.”

After several years of being understaffed, the Locks operations team is finally at full strength again. They’ve even got enough money for a few temporary hires to fill in during absences, Bergerson says.

“It was a revolving door for quite a while, so that really feels good.”

After all the smaller boats are secured three abreast on the large lock wall, Bergerson closes the gate behind them. He flips a switch to open the filling valves and warns the vessels to tend their lines as the water rises. When the chamber reaches lake level, it’s time to open the front gate, which stirs up strong currents.

“This is the scariest time for the operators and vessels,” he says. “I’ve seen a few lines snap.”

But everything goes smoothly, and the boats untie and head off to their destinations.

The Locks operate 24/7, and this shift runs until 11 p.m.

Even before the large lock is empty, another batch of pleasure boats is milling around waiting to make the opposite passage to Puget Sound. A tour boat captain hails the tower by radio to say he’s outbound with 94 passengers.

Bergerson instructs him to proceed to the small lock, and the crew gets ready to do it all again.

![David Chapman, project engineer with the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, walks in the utility tunnel that crosses from below the pumphouse in the Ballard Locks administration building to the other side of the large lock chamber. Regarding the administration building, Chapman says, “[People] don’t know there’s this deeply industrial heart to it.” (Karen Ducey / The Seattle Times)](https://images.seattletimes.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/09132023_lockstunnel_133606.jpg?d=780x520)