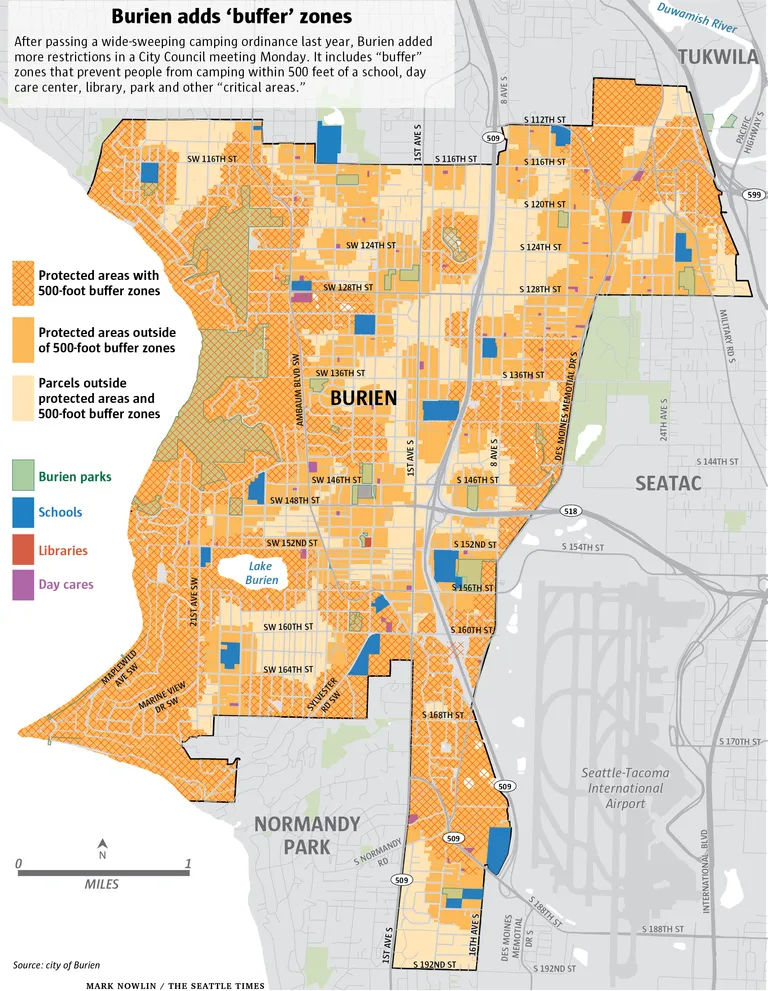

In a 5-2 vote Monday night, Burien’s City Council tightened its existing camping ban and added that people can’t sleep within 500 feet of schools, day-care centers, libraries, parks and other “critical areas.”

The changes go into effect immediately. These new “buffers” and protected areas across the city, which the city attorney said the city can modify as needed, leave scattered and fragmented patches of land for a growing homeless population to sleep on at night and will likely force people away from public places they rely on.

The city of Burien is currently being sued in King County Superior Court for its camping ordinance by three homeless people and the Seattle/King County Coalition on Homelessness, a regional advocacy organization. The lawsuit claims the ordinance “banishes” homeless people and inflicts “cruel punishment” that violates Washington’s Constitution.

These changes come after a year of turmoil and debate within the small South King County city over what to do about an unsheltered homeless population that has moved around the city. In less than a year, the city went from fretting about how to get people indoors to passing camping restrictions that create several barriers to living outside.

King County, which provides contracted law-enforcement service to the city of Burien, said it’s “currently evaluating the ordinance to ensure that it fits within the proper mission of the Sheriff’s office,” according to spokesperson Chase Gallagher.

“Burien adopted this ordinance with minimal notice to the public and no outreach to King County,” Gallagher said. “This is atypical.”

Burien did not immediately respond to King County’s assertion.

The King County Regional Homelessness Authority, which was designed to manage the county’s response to homelessness, said it’s “disappointed” in the council’s vote, according to spokesperson Lisa Edge.

“There are already limited opportunities in Burien for people living unsheltered to come inside and receive services,” Edge said. “This decision further pushes them out of Burien and into nearby areas.”

Councilmember Jimmy Matta made the motion to adopt the ordinance. He noted that homelessness is affecting cities across the United States and “across the world,” and said “we’ll just keep on looking for a solution that can bring some peace to this community.”

During a short discussion before the vote Monday, Burien Councilmember Hugo Garcia cited the lawsuit to help explain why he was voting “no” on the changes.

“So us making changes that are minimal at best to an ordinance that we are already being sued on is just bad decision-making, in my opinion,” Garcia said.

Councilmember Sarah Moore was the second dissenting vote, saying the ordinance does nothing to address the root causes of homelessness and does not provide people a safe place to be.

Before the vote, more than 30 Burien residents signed up to speak during public comment. The majority said they were opposed to the proposed changes. One person compared the “buffer” zones to redlining, a discriminatory practice that kept Black people from acquiring home loans and property.

“It’s really hard to be here and have your entire community turn their backs on you,” said homeless resident Marina, who didn’t provide a last name during public comment Monday. “I grew up in this town.”

Burien resident Karen Sinkula mentioned a video of newly elected Councilmember Linda Akey that recently received wide regional attention, calling it “embarrassing.”

Akey was filmed confronting homeless people sleeping on the sidewalk near her home in downtown Burien. She told one person, “I live here and you do not belong here. You are trespassing right now.”

Others residents told the council that this step would help address the public safety concerns they’ve shared.

One person, who only listed their first name as Marie on the public comment form, told Council, “I don’t bring my kids to the library anymore because it’s not a safe place for them to be.”

Since early February, several people have been putting down their belongings and sleeping in tents on sidewalks in Burien’s downtown after 7 p.m. and then packing up and moving somewhere else by 6 a.m., to stay in accordance with Burien’s camping ban. Burien is only allowed to give criminal infractions to people who violate the ban if there is available shelter to offer.

Most have been sleeping close to Burien’s City Hall and Library building. It’s similar to an encampment that formed outside City Hall more than a year ago, which originally sparked the city’s debate about how to handle the growing issue.

The adopted changes will likely displace this population because of the proximity to the Burien Library. These recent downtown campers moved there after a sanctioned encampment, which sheltered up to 65 people at its peak, closed after its three-month lease with Burien’s Oasis Home Church ended in early February.

The nonprofit behind the sanctioned encampment, Burien Community Support Coalition, said it is currently looking for a new home.

Near the end of 2023, Burien selected a piece of land owned by Seattle City Light to establish a tiny house village, which qualified the city to receive a $1 million offer from King County.

King County offered the money to help Burien address its unsheltered homelessness crisis. But it’s unclear when that could come online. A spokesperson for the city of Seattle said in early February that work is underway.