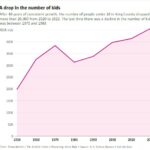

Did King County hit “peak kids” in 2020?

The 2020 census counted 456,000 people under 18 in King County, the highest number ever recorded. That isn’t a surprise, since the county’s population of children has increased steadily for decades.

But since then, there’s been a reversal.

New census data for 2022 shows the number of people under 18 dropped by more than 20,000 since 2020, falling to an estimated 436,000. That’s about the same as the county’s under-18 population in 2014.

“The funny thing about social trends is — nobody decides ‘I’m going to lower the national birthrate’ — they just decide to do something else this year instead of having a child,” said Philip N. Cohen, professor of sociology at the University of Maryland, College Park.

Compared with earlier generations, many people are choosing to do different things with their young adulthood instead of having kids, Cohen said. One reason for this is the increasing costs to raise children. And because of the costs, those who do have children are less likely to have a larger family.

Women in particular give up more by having children in young adulthood because it can have a greater impact on their earnings and career development, he added.

“We don’t have children because they’re beneficial to us economically anymore,” Cohen said. “Now we have children because we want to.” And a growing share of people are deciding they’re happier without kids.

The decline was fairly evenly spread out among age groups. Children under 5 decreased by 5%, as did those ages 5 to 14. The drop was a little smaller among those 15 to 17, down 3%.

It’s too soon to know if this is a long-term trend, but it is noteworthy, because the number of kids was increasing in King County for 40 years before this recent decline. The period of growth started after the 1980 census, which showed the under-18 population at around 313,000. The number had grown by more than 140,000 by 2020.

However, annual census data shows the rate of growth for the under-18 population slowed in the years leading up to the 2020 census. Since then, the numbers fell in both 2021 and 2022.

The last time the county had a decline in kids was in the 1970s, a decade marked by the “Boeing Bust,” which devastated the local economy. The aerospace giant, which was the area’s largest employer at the time, laid off 60% of its workforce in this period. The county’s rate of growth slowed as a result, and the number of children dropped by about 70,000 by 1980.

Like the Boeing Bust, the pandemic has also slowed the overall rate of growth in King County. But there are other factors that may be contributing to the recent decline in the county’s child population — factors that didn’t exist in the 1970s, and that could potentially make this decline more long-lasting.

Some of these are larger societal trends, and not unique to King County.

For example, Americans are getting married later, if at all, and an increasing share of adults are childless and do not expect to have children. As a result, fertility rates in the U.S. have been on the decline, and took a sharp downward turn during the pandemic.

Between 2005 and 2021, fertility rates dropped in all but two states, according to data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. In Washington, the fertility rate dropped from 63 to 52.4. The fertility rate is defined by the CDC as the total number of live births per 1,000 women aged 15-44.

At the local level, King County seems to have become less attractive to many families with children. The most obvious reason for this is the high cost of housing. In 2023, the median listing home price in King County was about $876,000, according to the Northwest Multiple Listing Service.

Of course, this makes it difficult for families who aren’t affluent to stay in, or move to, King County. The median income for a married couple with children in King County was $203,000 in 2022, according to census data.

Longtime Seattle resident David Meide and his wife, Susan Darling, are among those who have decided not to have kids. For the couple, who’ve been married since 2009, it wasn’t an agonizing decision.

“A lot of it was economic, but a lot of it was just personal preference,” Meide said. “I don’t think either of us felt compelled to have children, or that children would be our first priority.”

That was mainly because both Meide and Darling had a lot of outside interests, some of which are easier without kids, such as travel.

“I really think it’s a Seattle thing,” Meide said, and living in the city, he’s never felt any social pressure to have children. In fact, the “vast majority” of his friends in the area also don’t have kids, whether coupled or single.

With the high cost of housing locally and national trends like falling fertility rates, it’s not surprising to see the pattern of household growth in King County shifting away from families with children, and more toward other living arrangements. From 2015 to 2022, the number of King County households with children increased by just 2%, according to census data. Compare that with the number of one-person households in the county, which increased by 24%. Most of this increase in people living alone was in Seattle.

It’s not uncommon to find neighborhoods with very few children in the most urban areas of Seattle. In fact, the most recent data for census tracts, which averages data collected from 2018 to 2022, shows five tracts in Central Seattle with an estimate of zero children. These areas were in parts of Uptown, Belltown, South Lake Union and Capitol Hill, and are all typical urban neighborhoods of mostly young, unmarried adults living in apartments.

Note that it is possible there are a few kids in these areas, but the Census Bureau did not record any in five years’ worth of surveys.

There are still places in King County where you can find lots of kids. The areas with the highest concentration of children are in the suburbs to the east and south of Seattle.

The top census tract for kids is in Sammamish and includes the Lawson Park neighborhood. There are nearly 1,200 people under 18 here, representing 40% of the total population. This is an affluent area with a median household income of around $233,000, and 78% of households were owner-occupied. Married couples made up 93% of the households.

As expensive as it can be to raise a child in King County, there are still plenty of folks who do it on a modest income. The tract with the second-highest percentage of kids, at 38% of the population, was in Kent, and much less wealthy than Sammamish. This area, located to the east of Highline College, had a median household income of only $52,000. About 60% of homes were rented, and 52% of households were married couples.

In a tract in Eastern King County, in the Preston/Fall City area, kids also made up close to 38% of the population. This area is demographically closer to Sammamish, with a median household income of $186,000. Married couples made up 76% of households, and 87% of home were owner-occupied.